19 Cartoon Characters That Faded From Regular Rotation On American TV

Saturday mornings used to belong to cartoon characters who felt as familiar as cereal mascots and couch cushions.

They ruled the TV for a hot minute, then quietly vanished when tastes changed, rules tightened, or networks decided it was time to move on. Once upon a time, they had kids laughing in pajamas across America.

Today, mentioning them gets blank stares and a very hesitant, “wait… that sounds familiar.”

Important: Information in this article reflects widely reported publication dates, production credits, and commonly documented animation history available at the time of writing. Commentary focuses on shifts in programming, cultural standards, and rerun practices, which can vary by market, distributor, and era.

19. Happy Hooligan

A tin can perched on his head became the signature look for this lovable vagabond.

Frederick Burr Opper created this character in 1900, and Happy Hooligan stumbled through adventures with optimism despite constant misfortune. His kind heart never wavered even when luck abandoned him at every corner.

Later audiences largely moved on as animation studios chased flashier concepts. The tin can hat sits in cartoon history now, gathering dust alongside other relics from vaudeville-era humor.

18. The Katzenjammer Kids

Household pranks reached an artful extreme once Hans and Fritz entered the scene, leaving adults completely frazzled. Back in 1897, Rudolph Dirks introduced these troublemakers, placing them among the earliest comic characters to later make the leap into animation.

Slapstick chaos filled every panel as stereotyped dialect humor and nonstop scheming drove each gag forward. Changing cultural standards made the strip’s stereotype-based humor harder to package for modern kids’ programming.

Lazy Sunday mornings no longer feature frantic chases through living rooms, as the Captain and Mama faded from American screens in The Katzenjammer Kids.

17. Buster Brown

That pageboy haircut and Little Lord Fauntleroy suit made Buster Brown instantly recognizable in store windows and comic pages. His dog Tige became his partner in mischief, though Buster always learned moral lessons by story’s end.

Richard Outcault created this well-dressed scamp in 1902, and shoe companies loved slapping his face on their products.

Television animation moved past this preachy format as kids demanded faster action and fewer life lessons wrapped in fancy bows.

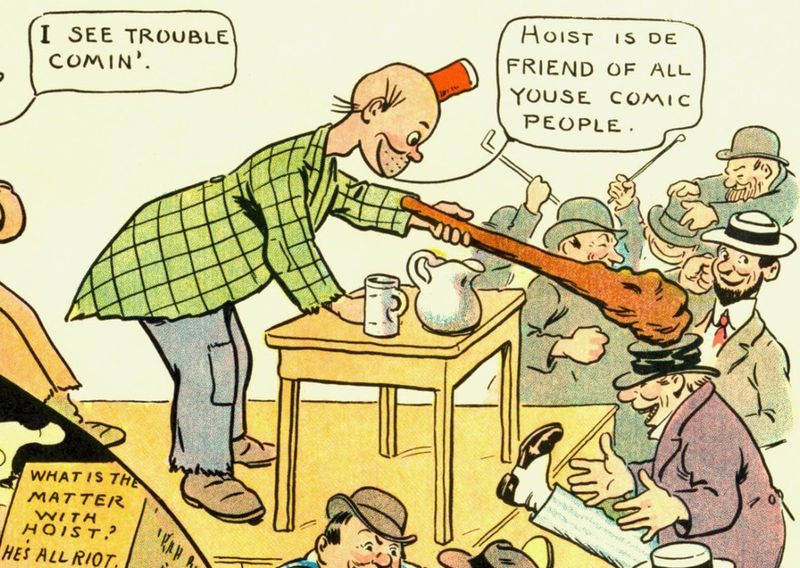

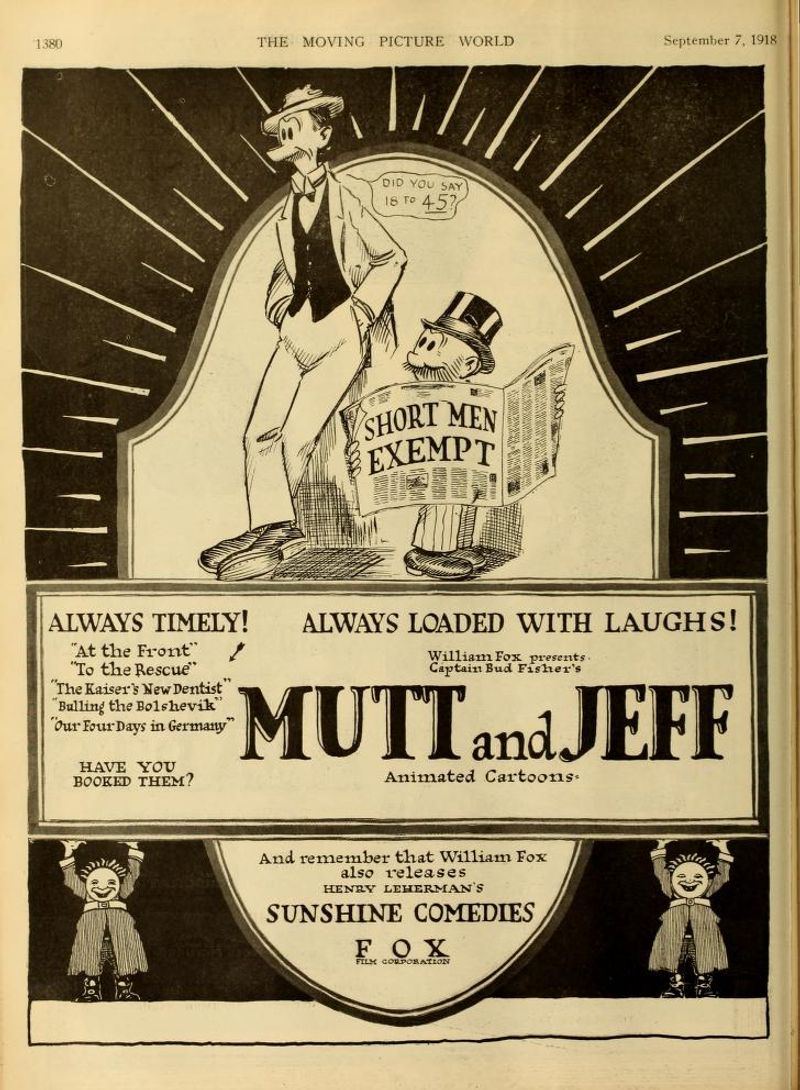

16. Mutt And Jeff

Comedy gold emerged in 1907 once Bud Fisher paired two wildly mismatched figures. Towering stature put Mutt beside Jeff like a flagpole next to a fire hydrant, letting physical contrast power every gag.

Vaudeville-style timing carried over smoothly into early animation shorts that ran ahead of feature films.

Over time, audiences started craving characters with richer personalities instead of relying only on visual jokes. Height-based humor gradually felt dated as television introduced layered storytelling, easing classic odd-couple routines like Mutt and Jeff out of the spotlight.

15. Colonel Heeza Liar

Tall tales spilled from his mouth faster than truth could catch up.

J.R. Bray Studios introduced this blustering fibber in 1913, making him one of the first recurring animated stars.

His wild adventures existed only in his imagination, but the Colonel sold every outrageous story with unwavering confidence. Silent film audiences ate up his pantomimed bragging, though his act lost steam when talkies demanded actual dialogue wit.

Modern viewers prefer their liars with sharper writing and less mustache twirling.

14. Bobby Bumps

Back in 1915, Earl Hurd introduced a freckled kid and his loyal pup to early animation audiences. Boundless enthusiasm pushed Bobby Bumps into everyday childhood adventures that rarely matched his actual skill level.

Cel animation techniques featured in these shorts helped revolutionize how animated stories were made at the time. Limited premise began to show strain once studios shifted toward characters built around stronger personalities and sharper quirks.

Morning television blocks eventually filled with cartoons offering brighter colors and bigger laughs, leaving Bobby Bumps behind as tastes moved on.

13. Farmer Al Falfa

Overalls and a scraggly beard defined this rural character who first appeared in 1915.

Paul Terry created Farmer Al Falfa as a rural comic archetype who stumbled through situations with more luck than sense. His farm became the backdrop for sight gags involving stubborn animals and broken machinery.

Urban audiences gradually lost interest in barnyard humor as cities grew and fewer families connected with agricultural life. The old farmer plowed his last field when networks decided country comedy belonged in the past.

12. Bosko

Round head, oversized eyes, and a whistling voice defined one of early sound animation’s most recognizable figures. Created in 1927 by Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising, Bosko arrived as Warner Bros. pushed headfirst into talking pictures.

Early designs drew on racial caricature conventions that are widely criticized today, an influence that makes modern audiences deeply uncomfortable.

Jazz-age musical numbers filled the shorts with lively energy, yet racial caricature elements could not withstand growing social awareness. Later TV packaging often avoided or de-emphasized the character because the imagery raised clear concerns for modern audiences.

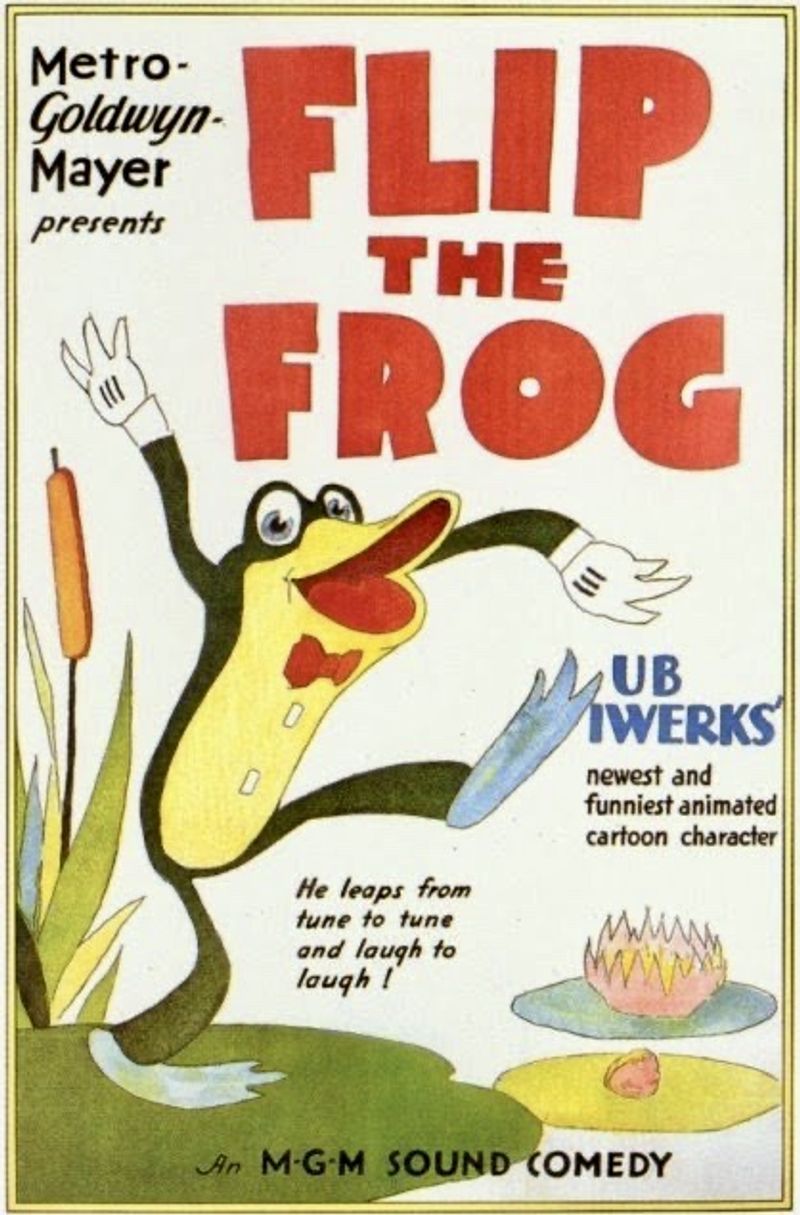

11. Flip The Frog

Ub Iwerks left Disney to create this amphibian star in 1930, hoping to rival Mickey Mouse’s success. Flip hopped through adventures with jazz soundtracks and fluid animation that showcased Iwerks’ technical brilliance.

His frog features gradually became more human as studios tested different designs.

The character never found a distinct personality beyond generic pluckiness, and audiences stayed loyal to more established cartoon stars. Flip gradually faded as audiences gravitated to better-defined stars.

10. Krazy Kat

Back in 1913, George Herriman introduced a feline philosopher caught in a logic-defying love triangle with a mouse and a dog.

Devotion flowed one way as Krazy adored Ignatz Mouse despite constant brick-throwing, while Offissa Pupp stood guard with unwavering loyalty.

Surreal desert backdrops and poetic dialogue elevated the strip into an artistic triumph unlike anything else on the comics page. Straightforward narratives appealed more to television audiences, leaving little patience for abstract reflections on unrequited affection.

Gentle weirdness and experimental artistry faded from view as Krazy Kat struggled to fit a medium built around clarity over imagination.

9. Little Nemo

Winsor McCay transported readers into spectacular dreamscapes through this pajama-clad adventurer starting in 1905.

Every strip ended with Nemo tumbling from bed, waking from impossible journeys through Slumberland’s architectural wonders. McCay’s detailed artwork set standards that animation struggled to match for decades.

Television cartoons lacked the budget for Nemo’s intricate fantasy worlds, settling instead for simpler backgrounds and faster production schedules. Dreams that once filled newspaper pages became too expensive to animate for weekly broadcast slots.

8. Bimbo

Floppy ears and a button nose marked Betty Boop’s earliest animated sidekick at Fleischer Studios.

Original status once belonged to Bimbo, before rising fame around Betty Boop pushed him out of the spotlight. Romantic pursuit created uneasy dynamics after mid-1930s censorship tightened rules around acceptable content.

Flirtatious behavior toward a human character later raised concerns among broadcast standards committees revisiting early cartoons.

Solo airings became the easier option, leaving Bimbo behind rather than explaining why a cartoon dog kept making passes at his co-star.

7. Betty Boop

That baby voice and garter belt made Betty Boop a jazz-age sensation starting in 1930. Max Fleischer created her as a caricature of flapper culture, complete with suggestive songs and revealing outfits that pushed pre-Code Hollywood boundaries.

Censorship rules forced her hemline down and her personality into wholesome territory by 1934.

Many modern programmers have treated the shorts cautiously because the character’s styling and adult themes can feel out of step with contemporary standards. Her vintage shorts largely disappeared from rotation as networks avoided uncomfortable conversations about outdated gender portrayals.

6. Gertie The Dinosaur

Back in 1914, Winsor McCay brought a brontosaurus to life and created one of animation’s first true personalities. Responding to vaudeville-style commands, Gertie danced, ate rocks, and charmed audiences with a sense of dinosaur charisma that felt startlingly real.

Playful disobedience gave her the spark of life, making the character seem alive rather than merely drawn.

Over time, novelty alone stopped being enough as viewers began expecting ongoing stories and recurring casts instead of isolated spectacles. Historical importance endured, yet Gertie the Dinosaur stayed a curiosity rather than a television staple, too primitive for modern programming blocks despite a groundbreaking legacy.

5. Koko The Clown

Max Fleischer’s inkwell birthed this clown in 1919 using rotoscope technology that traced live-action footage. Koko bounced between cartoon world and reality, interacting with his animator’s hands in surreal meta-comedy.

His rubbery movements and shape-shifting abilities showcased early animation’s limitless potential.

Television audiences wanted consistent character designs, not morphing figures that changed appearance scene to scene. The technical innovation that made Koko special became a liability when networks sought reliable brand mascots for merchandising opportunities.

4. Underdog

Shoeshine boy turned caped hero whenever Sweet Polly Purebred needed rescue from Simon Bar Sinister’s schemes.

Underdog debuted in 1964, speaking in rhyming couplets while battling villains with his super energy pill. His bumbling alter ego contrasted sharply with his confident superhero persona, creating comedy through dual identities.

Reruns faded as networks prioritized newer properties with stronger merchandising potential. The humble hero who spoke in verse couldn’t compete when action figures and lunch boxes drove programming decisions more than nostalgic charm.

3. Oswald The Lucky Rabbit

Long ears and a mischievous grin marked Walt Disney’s first major cartoon star in 1927.

Silent adventures starring Oswald the Lucky Rabbit carried a playful personality that clearly foreshadowed Mickey Mouse’s later success.

Contract disputes changed everything, costing Disney the rights and sending Oswald to Universal Studios while a certain mouse was created instead.

Ownership limbo and legal tangles kept the rabbit off television for decades, blocking proper distribution and public rediscovery. Reacquisition finally came in 2006, yet generations had already grown up unaware of the lucky rabbit who helped start it all at The Walt Disney Company.

2. Popeye

Spinach-fueled strength and a corncob pipe made this sailor an icon starting in 1929.

Popeye muttered through adventures protecting Olive Oyl from Bluto’s bullying, teaching kids about healthy eating through exaggerated muscle inflation.

His aggressive solution to every problem involved punching opponents into submission after downing canned vegetables. Modern concerns about violence in children’s programming reduced his television presence significantly.

Networks questioned whether teaching kids to solve conflicts with fists sent the right message, even when powered by leafy greens.

1. Felix The Cat

That magic bag of tricks and perpetual grin made Felix one of silent animation’s biggest stars starting in 1919. Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer created a cat who walked with hands behind his back, whistling through adventures that needed no dialogue.

His transition to sound cartoons stumbled badly, losing the visual poetry that defined his appeal.

Television revivals in the 1950s and 1960s couldn’t recapture the original’s charm, feeling dated compared to modern cartoon sophistication. Felix became a nostalgic symbol rather than appointment viewing for new generations.