20 Classic Universal Monster Films That Haven’t Left The Conversation

Universal’s monsters never really left. Pale faces, stiff walks, and iconic entrances still haunt pop culture and midnight screenings alike.

Nearly a century later, fans dress up, argue favorites, and pretend they’re not scared while watching through their fingers.

Disclaimer: This article discusses classic horror films and their cultural impact, using widely reported production details and commonly cited film-history notes where available.

Some behind-the-scenes anecdotes and long-circulating stories may vary by source, so details presented as “legend” or “often discussed” should be understood as part of the films’ historical chatter rather than as fully documented fact.

20. Dracula (1931)

Bela Lugosi’s cape swirls across the screen like ink spilling into water.

The Hungarian actor turned a Transylvanian vampire into Hollywood royalty with nothing but a piercing stare and an accent sharp enough to make the dialogue instantly recognizable. Later film vampires either intentionally pushed against or mimicked his act, which established the template.

Late-night cable runs kept this one alive for generations who never stepped foot in a 1930s theater. That creaky castle staircase still gets quoted in everything from cartoons to candy commercials.

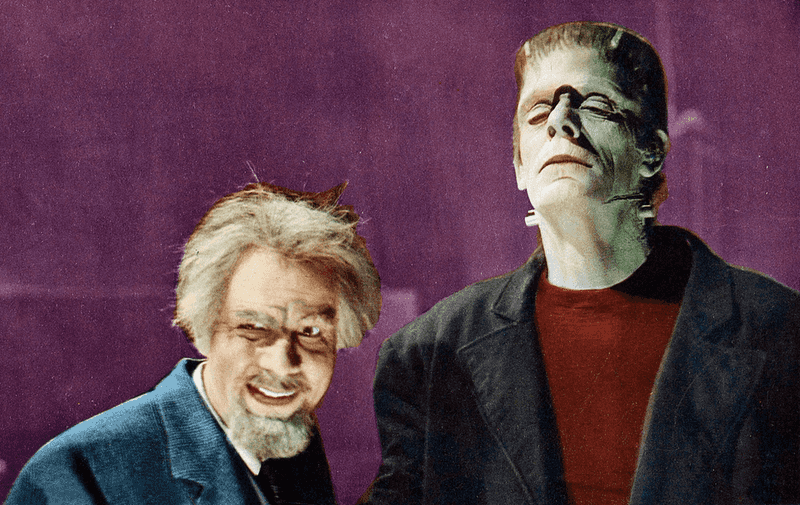

19. Frankenstein (1931)

Seven layers of makeup and forty pounds of costume weigh heavily as Boris Karloff shuffles into frame, turning a flat top head and neck bolts into universal shorthand for monster.

Under James Whale, Frankenstein reshapes Frankenstein into a meditation on ambition racing past common sense. Crackling electricity and towering machinery in the laboratory scene set a template that countless mad scientist films would echo for decades.

Grunts and groans carry more weight than pages of dialogue, proving physical performance can speak louder than words ever could.

18. Bride Of Frankenstein (1935)

Elsa Lanchester’s lightning-bolt hairdo took three hours to build each morning.

She hisses at her intended groom for maybe five minutes of screen time, yet that image outlasted countless leading ladies with triple the dialogue. James Whale returned to direct a sequel that somehow improved on perfection.

The film mixes Gothic horror with sly comedy in ways that shouldn’t work but absolutely do. That final laboratory explosion remains one of cinema’s most operatic crescendos, complete with crumbling stone and heartbreak.

17. The Wolf Man (1941)

Hours vanished in a makeup chair as Lon Chaney Jr. endured yak hair glued to his face one strand at a time by Jack Pierce. Lap-dissolve ‘progressive makeup’ shots gave physical form to terror, effects that still impress practical makeup fans today.

Fear of losing control after nightfall defines Larry Talbot’s curse, tapping into anxieties that feel painfully human.

Silver tipped cane rose to iconic status while a tragic ending showed how monsters can wound hearts as deeply as they frighten. Menace settles thick over foggy moors in The Wolf Man, sealing atmosphere that refuses to fade.

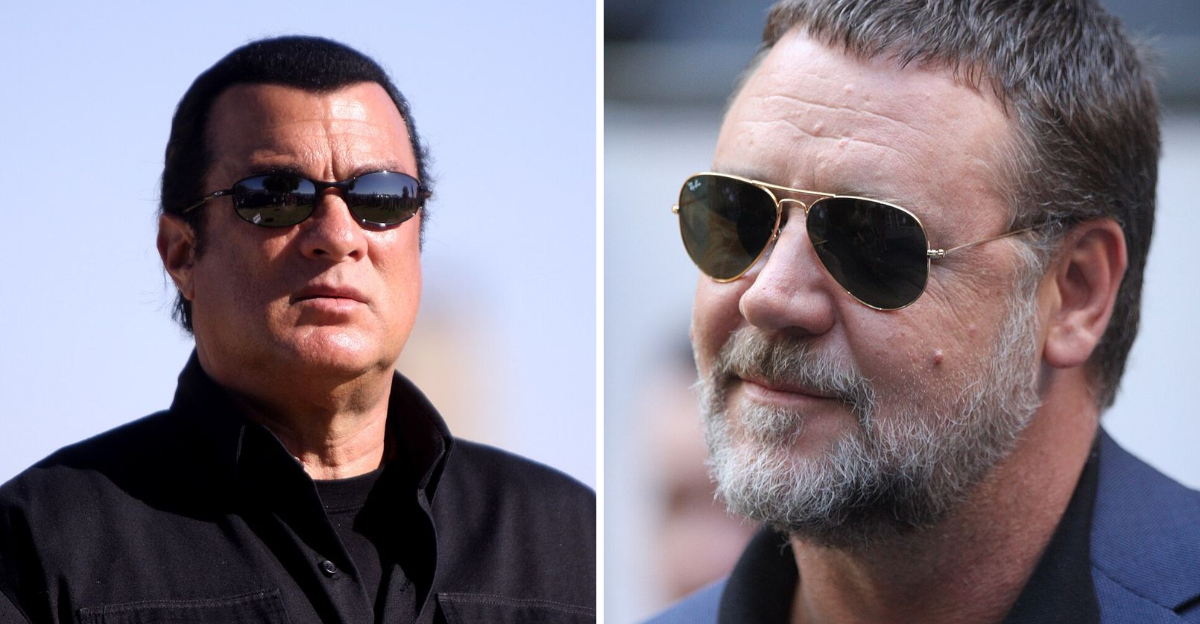

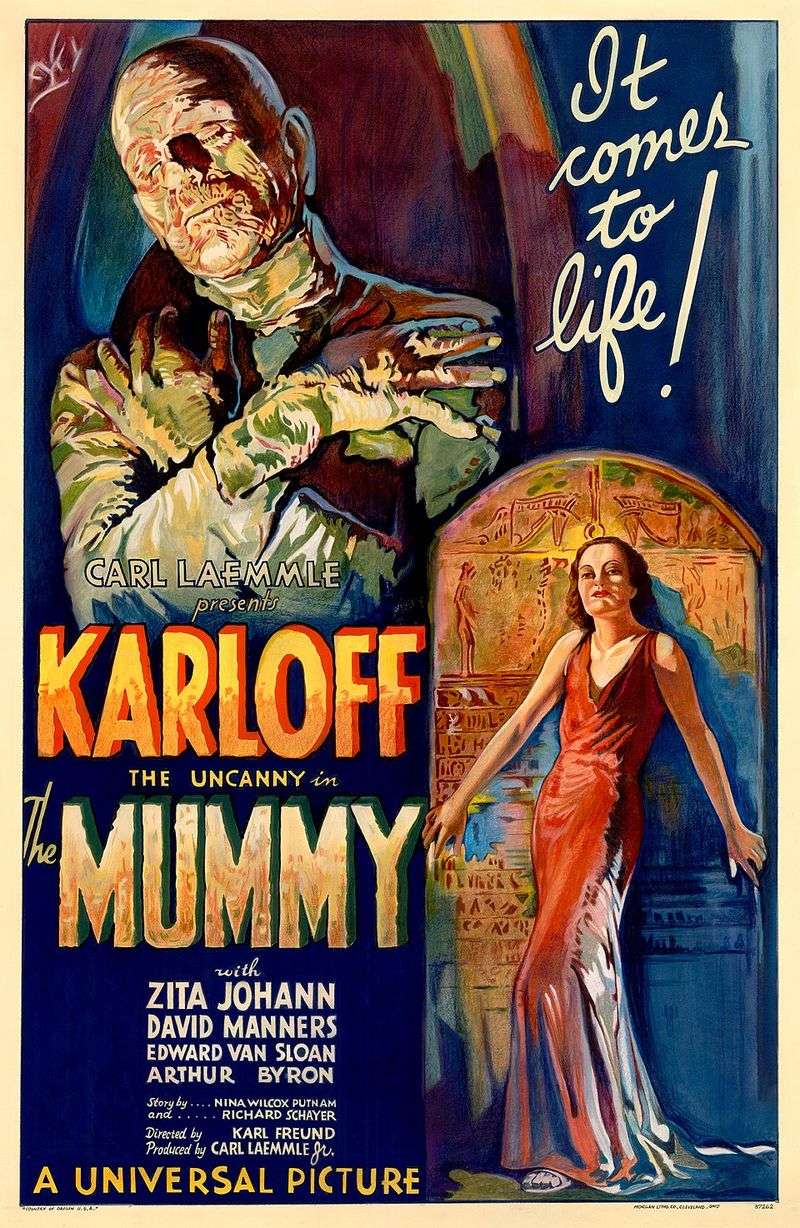

16. The Mummy (1932)

Boris Karloff traded neck bolts for rotting bandages and a backstory spanning three thousand years.

The opening scene where Imhotep’s eyes snap open remains a masterclass in building dread with a single close-up. Karloff’s gaunt face under layers of cracked makeup suggested something older than pyramids and twice as patient.

The film blended Egyptology craze with forbidden-love tragedy, proving curses work best when they’re personal. That slow, deliberate walk became the template for every shuffling undead creature Hollywood cranked out afterward.

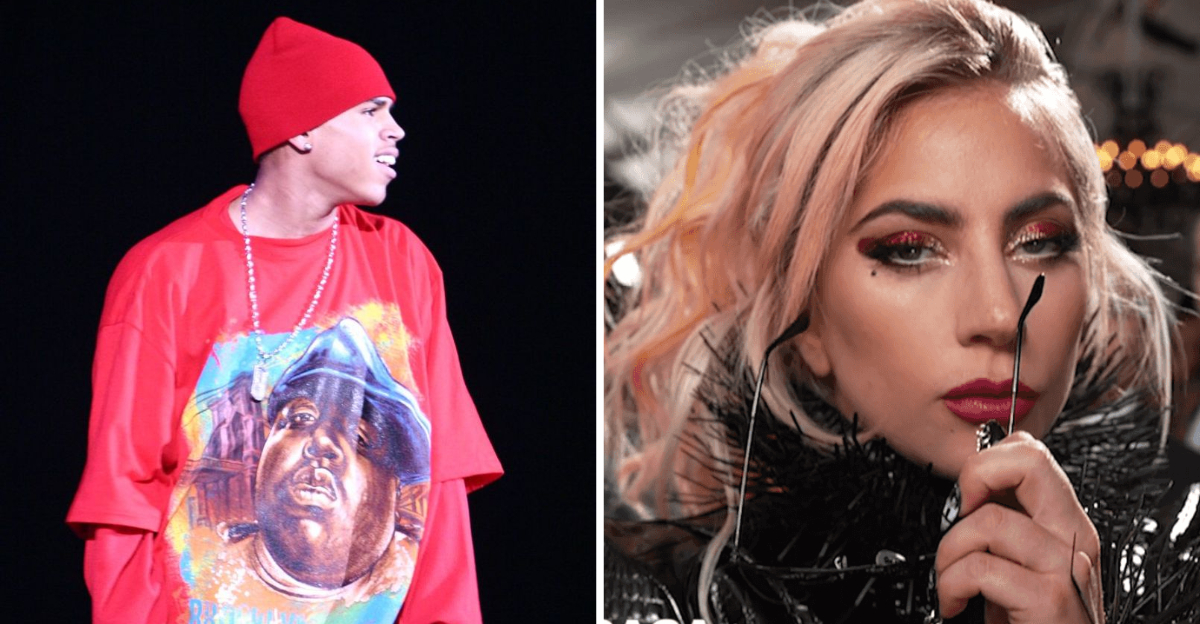

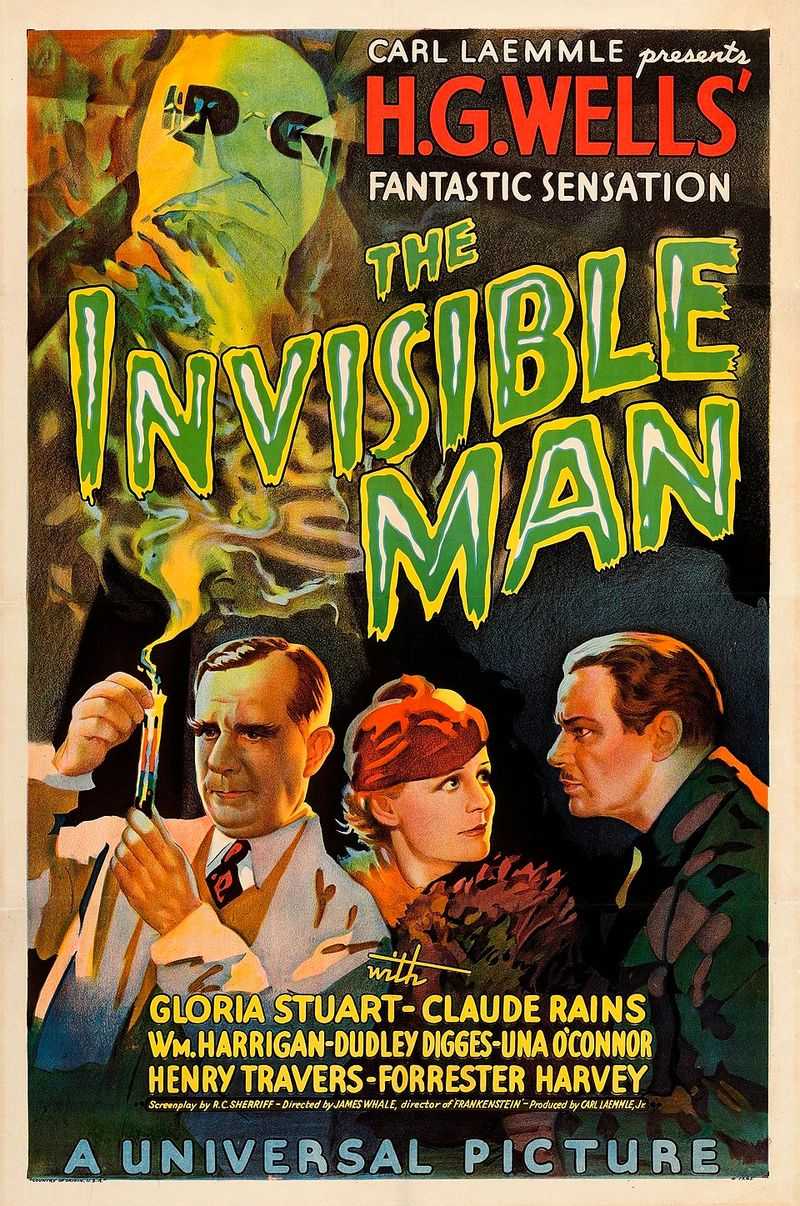

15. The Invisible Man (1933)

Unseen presence delivers one of cinema’s greatest performances, with Claude Rains withholding a face until the final seconds. Wires, black velvet, and sheer ingenuity let special effects teams pull off a man vanishing in plain sight.

Under James Whale, The Invisible Man reshapes The Invisible Man into a cautionary study of power and isolation.

Unraveling bandages still earn homages in modern films chasing that same slow revelation.

Manic laughter echoing through empty rooms proves terror does not require a monster suit to grip an audience.

14. Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954)

Rising from the Amazon, the Gill-man feels like evolution caught mid sketch, all scales and webbed claws.

Originally filmed in 3D, an underwater ballet with Julie Adams drifts into unsettling romance that somehow works in the creepiest possible way. Months of work went into a rubber suit perfected by Milicent Patrick, even as studio politics delayed proper credit for decades.

Influence spread far beyond Creature from the Black Lagoon, echoing through later films that borrowed its silhouette and mood.

Murky and primordial, the Black Lagoon itself functions as a living presence, guarding secrets that feel better left underwater.

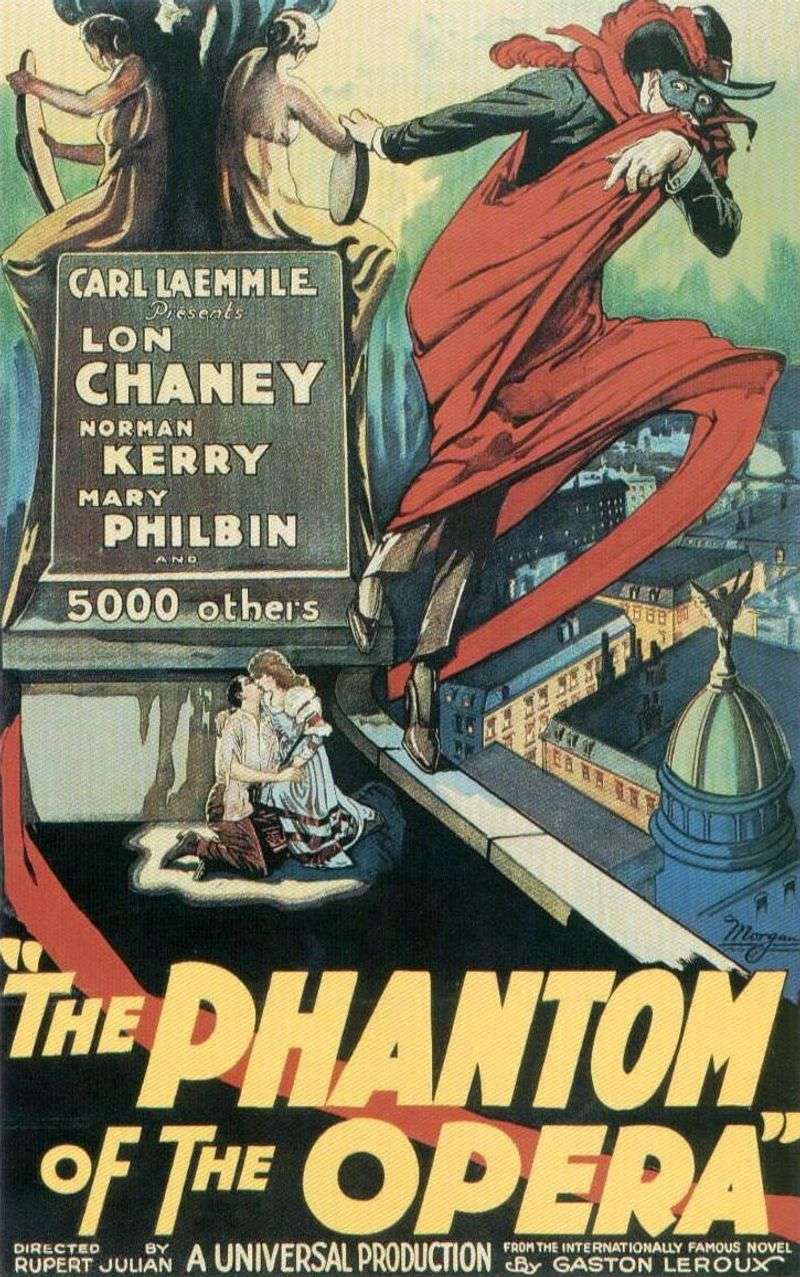

13. The Phantom Of The Opera (1925)

Lon Chaney Sr. designed his own skull-face makeup using wire, putty, and sheer dedication to suffering for art.

The unmasking scene caused audience members to faint in theaters, a marketing department’s dream come true.

Silent films relied on visual storytelling, and Chaney’s twisted features spoke volumes without a single word of dialogue. The chandelier crash remains a practical-effects triumph that modern CGI crews study for inspiration.

Paris Opera House never looked so Gothic or so doomed.

12. Son Of Frankenstein (1939)

Final turn arrives as Boris Karloff steps back into the Monster’s role, joined by Basil Rathbone as a conflicted son and Bela Lugosi as Ygor, marked by a damaged neck and a fierce stare.

German Expressionist influence dominates production design, with twisted shadows and impossible angles turning every room into a waking nightmare. Greasy charm and a shepherd’s flute nearly let Lugosi’s Ygor steal the show outright.

Proof lands that sequels can deepen mythology rather than recycle old shocks, with laboratory imagery that later shaped Tim Burton’s visual language decades on.

11. Dracula’s Daughter (1936)

Gloria Holden plays Countess Marya Zaleska with tragic elegance, a vampire who genuinely wants to break free from bloodlust. The film explored compulsion and inner conflict years before Hollywood had the vocabulary for such themes.

Her attempts at reform through hypnotherapy sessions feel surprisingly modern for a 1930s monster flick.

The atmospheric London fog and art-studio scenes added sophistication to creature-feature conventions. Holden’s performance framed vampirism as burden rather than power, a perspective echoed in later vampire fiction.

10. Abbott And Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948)

Stumbling through a wax museum, Bud Abbott and Lou Costello discover displays hiding real monsters rather than harmless replicas.

Horror plays straight while comedy supplies chaos, creating a balance that sounds impossible yet lands as pure movie magic.

Final turn as Dracula arrives with Bela Lugosi, joined by Lon Chaney Jr. stepping back into the Wolf Man’s curse. Slapstick chases through castle corridors set a blueprint later monster comedy mashups continue to follow.

Fun sneaks into every shadow as even the monsters seem aware of their legacy, occasionally winking at it while the chaos unfolds.

9. Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man (1943)

Awakening from a grave sends Larry Talbot searching for a cure, only to discover Frankenstein’s Monster preserved in ice. Genuine pathos comes through as Lon Chaney Jr. inhabits the cursed werewolf, while Bela Lugosi finally steps into the Monster’s towering platform boots.

Climactic collision between wolf and creature delivers exactly what Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man promises on the marquee.

Long before shared universes became a marketing term, Universal linked its monsters together, punctuating folk dancing festival scenes with lurking horror that amplifies both moods at once.

8. The Ghost Of Frankenstein (1942)

Lon Chaney Jr. inherited the Monster role from Karloff, bringing more brute force than tragic poetry to the part.

Cedric Hardwicke played yet another Frankenstein heir trying to fix grandfather’s mistakes while somehow making them worse. The brain-transplant plot gets delightfully absurd, with Ygor attempting to hijack the Monster’s body for himself.

The laboratory equipment reached new heights of crackling electrical excess, all spinning wheels and Jacob’s ladders. The ending twist where things go spectacularly wrong became a franchise tradition.

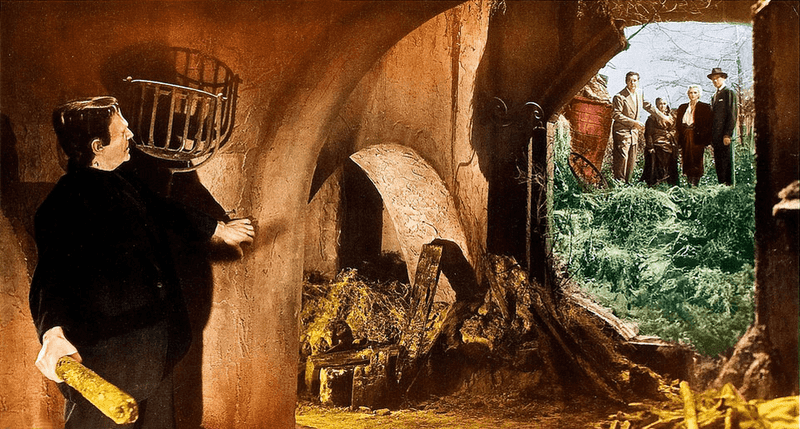

7. House Of Frankenstein (1944)

Everything collides when Universal Pictures packs its monsters into a single film that plays like a Gothic horror variety show. Dracula, the Wolf Man, Frankenstein’s Monster, a mad scientist, and a hunchback crowd the screen within a plot that barely holds together yet never stops entertaining.

Shift in casting places Boris Karloff back as a villain rather than the Monster, lending weight and authority to the chaos. Traveling horror show framing turns House of Frankenstein into a macabre anthology, hopping from creature to creature with carnival energy.

Overworked practical effects teams delivered transformation scenes and creature reveals that continue to impress long after the curtain fell.

6. House Of Dracula (1945)

A well-meaning doctor attempts to cure Dracula and the Wolf Man using science instead of stakes and silver bullets. The Monster shows up frozen in a cave because apparently nobody stays dead in these films.

Onslow Stevens plays the physician with tragic nobility, trying to help monsters who might be beyond saving.

The laboratory scenes reached peak mad-science excess with bubbling beakers and electrical storms on demand. The film helped close out the studio’s later cycle of mostly straight monster entries, right before the tone shifted more openly toward lighter crossovers.

5. Werewolf Of London (1935)

Henry Hull transforms into a werewolf six years before Lon Chaney Jr. made the role iconic, but with a more refined, almost dapper approach.

The London setting traded foggy moors for city streets, proving lycanthropy works just as well in urban environments. Hull’s makeup kept him more human-looking than later wolf-men, emphasizing the man trapped inside the beast.

The botanical angle with Tibetan flowers added an exotic twist to curse mythology. Jack Pierce’s makeup design influenced every werewolf transformation that followed.

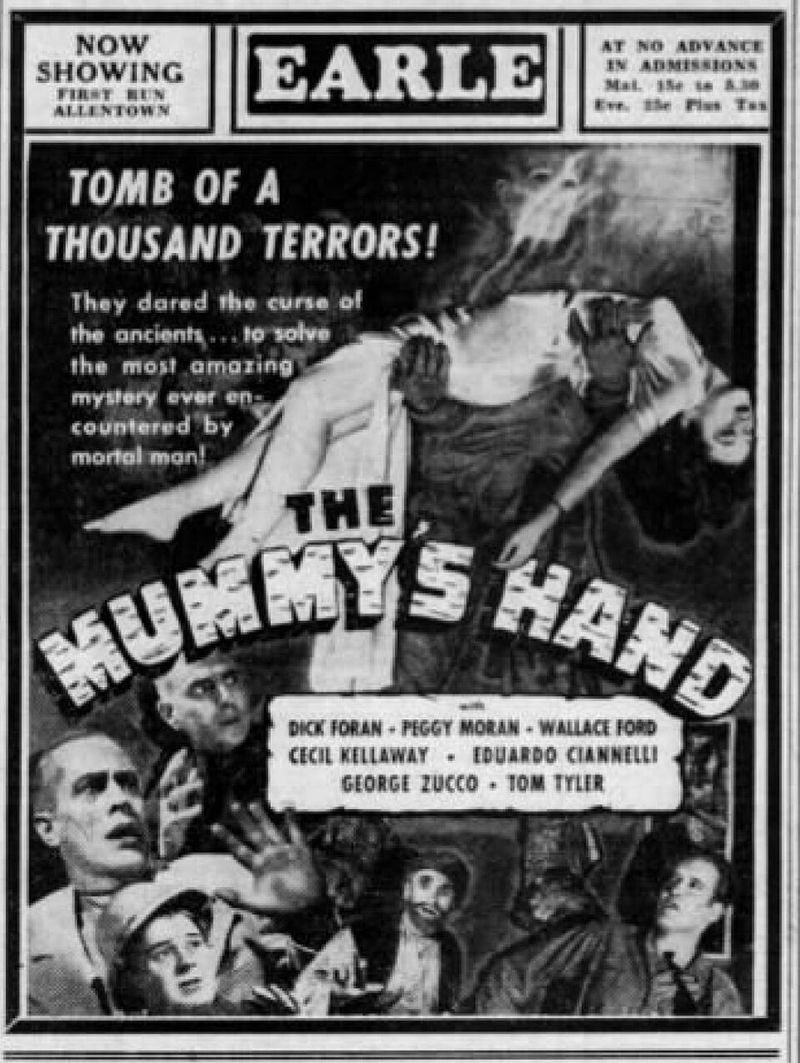

4. The Mummy’s Hand (1940)

Mummy duties passed to Tom Tyler, who embodied Kharis as a cursed high priest condemned to shamble through eternity guarding a forbidden tomb.

Atmosphere shifted away from Gothic dread toward adventure serial momentum, complete with wisecracking heroes and classic damsel peril. Budget limits forced reuse of footage from The Mummy, yet clever editing stitched old material into something that still functioned.

Tana leaves emerged as a control mechanism that powered multiple sequels and tied the mythology together.

Slow, methodical stalking defined The Mummy’s Hand, influencing zombie cinema decades before Romero reshaped the undead shuffle.

3. The Invisible Man Returns (1940)

Vincent Price made his horror debut as an innocent man turned invisible to clear his name of murder charges.

The special effects improved on the original with smoother disappearing acts and more ambitious wire work. Price’s distinctive voice carried scenes where no actor appeared on screen, proving he could command attention without physical presence.

The film balanced thriller elements with sci-fi horror, adding wrongful-conviction stakes to invisibility chaos. That coal-mine climax where the invisible man gets covered in dust remains cleverly conceived.

2. The Old Dark House (1932)

Shelter from a storm brings stranded travelers into a Welsh mansion overflowing with secrets and unstable residents under James Whale’s precise control.

Mute menace replaces monster makeup as Boris Karloff while a troubled butler whose volatility proves terror does not need prosthetics. Gothic mansion design left fingerprints on haunted house cinema stretching from Psycho to The Haunting.

Pre Code freedom allowed risqué dialogue and dark humor to coexist before later censorship erased such edges. Thunderstorms and creaking floorboards build dread through suggestion, letting atmosphere do the work instead of relying on jolts.

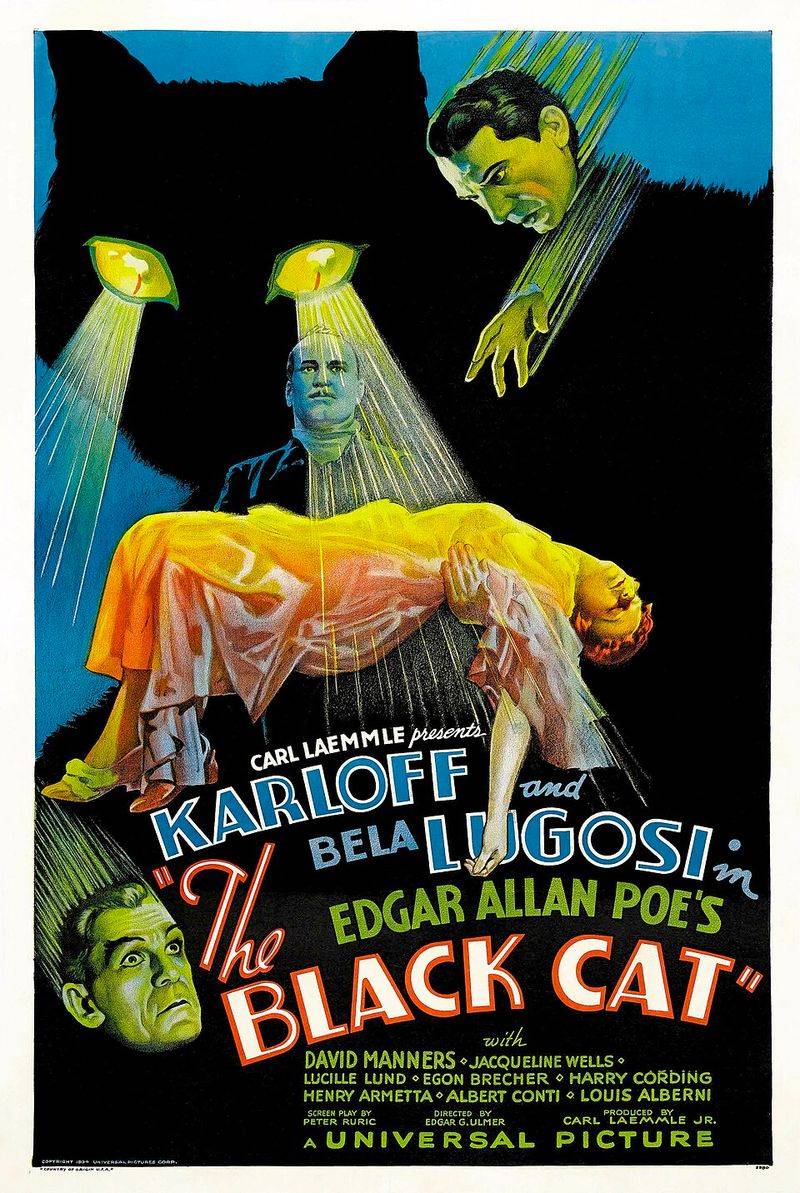

1. The Black Cat (1934)

Shared screen time finally arrives as Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi collide in a fever dream that only loosely resembles Edgar Allan Poe’s original story. Satanism, wartime betrayal, and a sleek modernist house built atop a World War I mass grave drive a plot that feels deliberately unmoored.

Art Deco geometry clashes with Gothic horror tradition, creating visual tension that feels unsettling rather than elegant.

Occult themes replace sympathy as Karloff inhabits a sinister architect, while Lugosi channels revenge fueled obsession, both actors clearly relishing the chance to chew every inch of scenery. Commercial success followed regardless, as The Black Cat became Universal’s biggest hit of 1934 despite narrative leaps and deeply disturbing undertones that linger long after the final frame.