How Sushi Traditions Differ In Japan And China

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the sushi showdown.

In one corner, Japanese sushi enters with quiet precision, centuries of discipline, and rice shaped like a black belt in minimalism.

In the other, China’s contender bursts in with bold rolls, bigger flavors, and food court confidence that plays to the crowd.

Same dish, two styles, totally different game plans. Pick a side before the first bite.

1. Core Definition And Identity

Imagine standing over two plates that barely seem related. In Japan, sushi centers on vinegared rice paired with a topping or filling, where balance and restraint carry the conversation.

In many mainland Chinese cities, sushi is most commonly encountered as an imported Japanese category, so definitions shift according to restaurant formats and local taste expectations rather than a long-standing domestic tradition.

Comparing them feels like setting a haiku beside a freestyle rap. Shared ingredients connect both, yet the rules guiding each approach sit worlds apart.

2. Origin Story And Historical Framing

Japan’s mainstream story often runs through older fermented forms, then into vinegar-seasoned rice and modern sushi culture. China gets described in scholarship as a place where Japanese cuisine actively localizes into new hybrid dining patterns rather than being preserved as a fixed ritual.

One country guards the recipe.

The other remixes the track. Both approaches honor food, just through completely different lenses that reflect centuries of separate culinary evolution.

3. Signature Classic Form

In Japan, the modern icon remains nigiri, rooted in Edo-period innovation and shaped by fast, hand-formed service at the counter.

Across China, everyday visibility often tilts toward rolls and set menus, especially in casual dining, takeout, and chain settings, formats that travel well and read clearly on a menu board.

Mastery defines nigiri, demanding precision and speed from a chef working face to face with diners. Consistency defines rolls, built for visual appeal and steady execution beneath bright food court lights.

4. Rice Seasoning Emphasis

Careful attention in Japan turns sushi rice known as shari and its vinegar seasoning into a craft foundation rather than background detail.

Many diners in China encounter sushi through chains and takeout, which allows the rice profile to feel more flexible in practice as consistency and convenience often outrank strict regional shari traditions. Quiet precision defines one philosophy, while practical reliability defines the other on a busy Tuesday lunch break.

5. Setting: Counter Culture Vs Chain Culture

At the heart of Japan’s dining culture stands the sushi counter experience, often featuring chef-selected courses in higher-end settings.

Scalable chain formats shape much of China’s sushi landscape, allowing restaurants to expand across cities while standardizing the experience.

Dinner theater energy defines one setting. Quick efficiency defines the other, perfectly suited to grabbing lunch between errands and matching the pace of everyday life.

6. Conveyor-Belt And Quick-Service Norms

Conveyor-belt sushi became a widely popular everyday format in Japan in many places, making speed and variety the whole point.

China has embraced the same high-throughput model via international and Japan-origin chains operating in Mainland China and nearby markets.

Watching plates glide past you never gets old, whether you’re in Tokyo or Shanghai.

It’s efficiency wrapped in novelty.

7. Sauces And Add-Ons

Modern creativity exists in Japan, yet classic presentations often favor restraint, with soy sauce and wasabi applied in a considered way.

Localization within China’s Japanese restaurant culture encourages bolder flavor cues such as extra sauces and richer textures, helping the cuisine settle comfortably into local tastes.

Subtlety defines one side, spectacle defines the other, and loyal fans on both ends would not trade their preference for anything.

8. Etiquette And Pacing

Sushi etiquette in Japan often emphasizes eating each piece promptly and respecting the intended bite size, almost like following choreography at a counter.

Casual group meals and quick-service settings shape expectations in China, where etiquette feels more relaxed and depends heavily on the restaurant rather than a formal ritual.

Homework and quiet awareness tend to define Japan’s approach. Hunger and good friends tend to define China’s.

9. Ingredient Expectations: Raw Vs Cooked

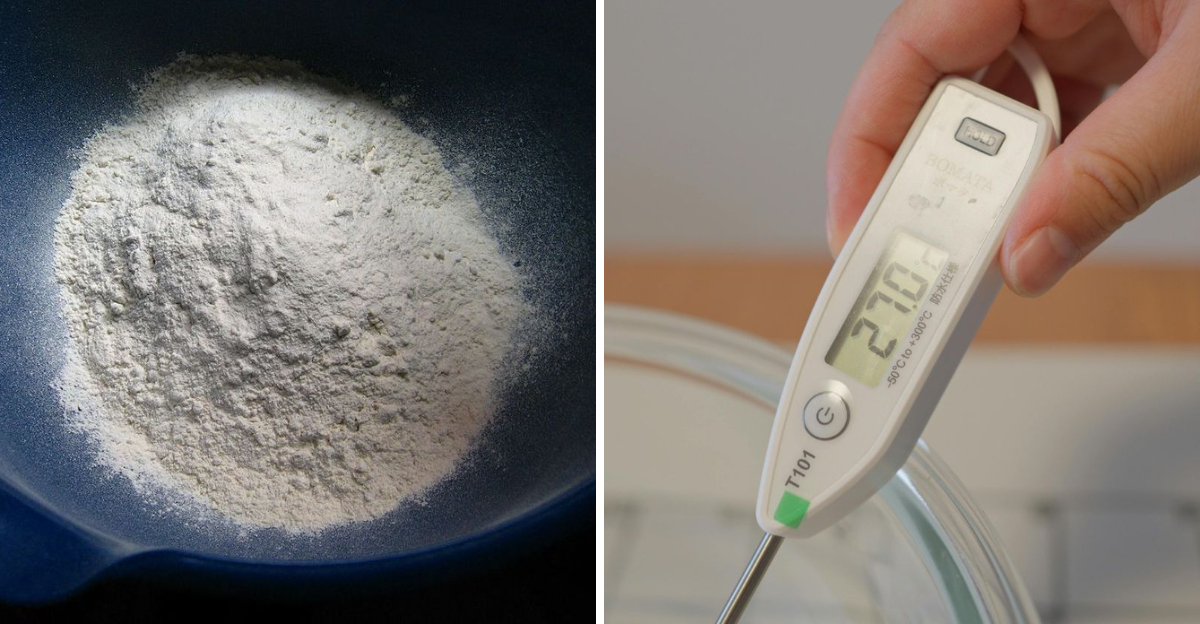

Careful handling and precise temperature control shape how Japan presents raw seafood, sometimes to a level that feels almost obsessive.

Mainstream sushi consumption in China often expands the comfort zone with more cooked, seared, or sauce-forward options, reflecting how localization influences restaurant practice. Raw fish purists and cooked-protein fans can both find their happy place, simply in different dining rooms across different cities.

10. Regional Styles And Named Traditions

Regional identity shapes sushi culture in Japan, where Edo-style nigiri associations, older fermented methods, pressed forms like oshizushi, and tofu-pouch inari carry visible layers of history.

Practice in China feels more contemporary and city-by-city. What appears common in one district can look different in another, shaped by chains, imported trends, and local preference patterns that shift quickly.

11. Local Signifiers And Menu Language

Menu language in Japan often points toward specific fish cuts, preparation methods, and seasonal choices that require insider knowledge to decode fully.

By comparison, menus in China frequently spotlight recognizable roll styles and photogenic items, since many guests encounter sushi first as a modern and cosmopolitan dining option. One approach teaches.

Another approach sells, and both strategies serve their target audience and dining culture effectively.

12. A Clear China Note That Often Gets Mixed In

A raw-fish celebration dish like yusheng or lo hei often gets associated with Chinese New Year in Chinese communities, but it’s not sushi at all.

It’s its own thing that sometimes gets mentioned in the same raw fish conversation, which can confuse newcomers.

Think of it as a distant cousin who shows up at family reunions but lives in a completely different neighborhood.

Note: This article compares broad dining and cultural trends and may simplify regional differences Details can vary by city, restaurant, and individual practice, and traditions evolve over time.

The content is provided for general informational and entertainment purposes and is not legal, financial, or professional advice.