14 Movie Adaptations That Earned Criticism From Their Own Authors

When books become movies, magic can happen on screen.

But sometimes the authors who wrote those beloved stories feel disappointed by what Hollywood did with their work.

Here are stories of writers who spoke out against the film versions of their own creations.

Note: Insights provided here serve as a snapshot of how famous authors have navigated the transition from page to screen.

This overview aims to provide entertaining context rather than a definitive historical record of an author’s professional sentiments.

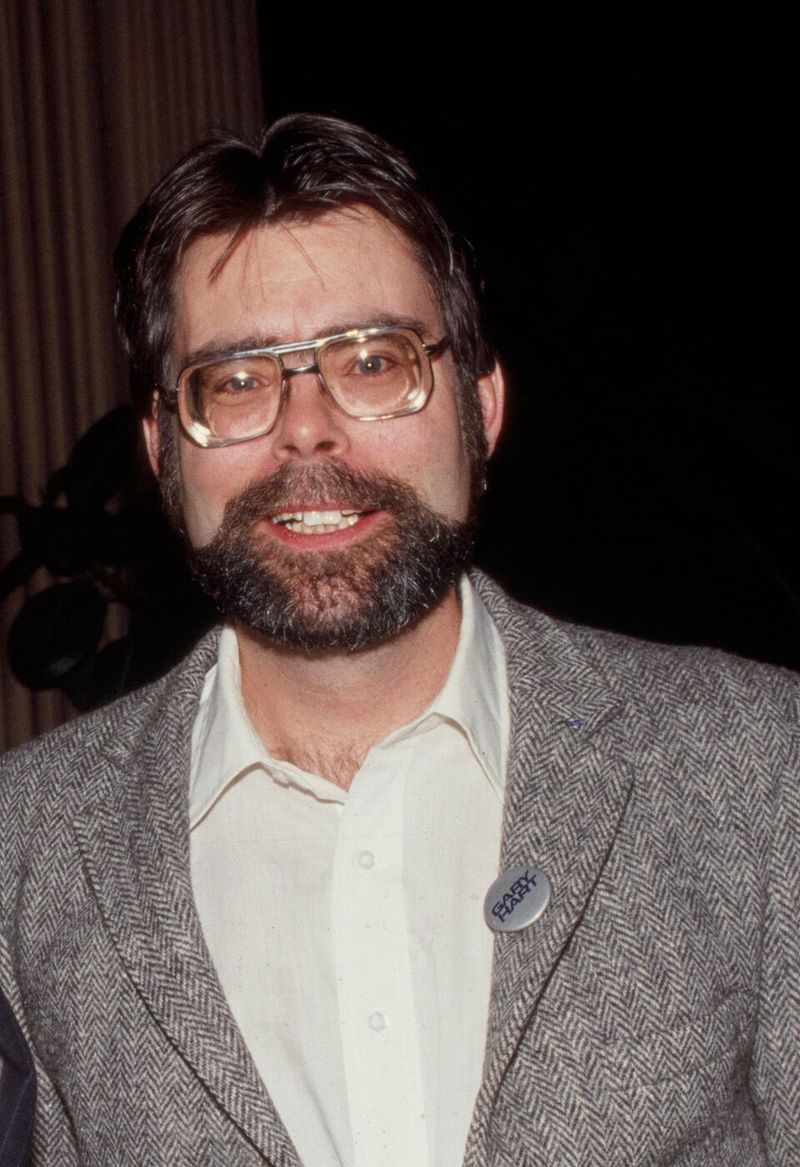

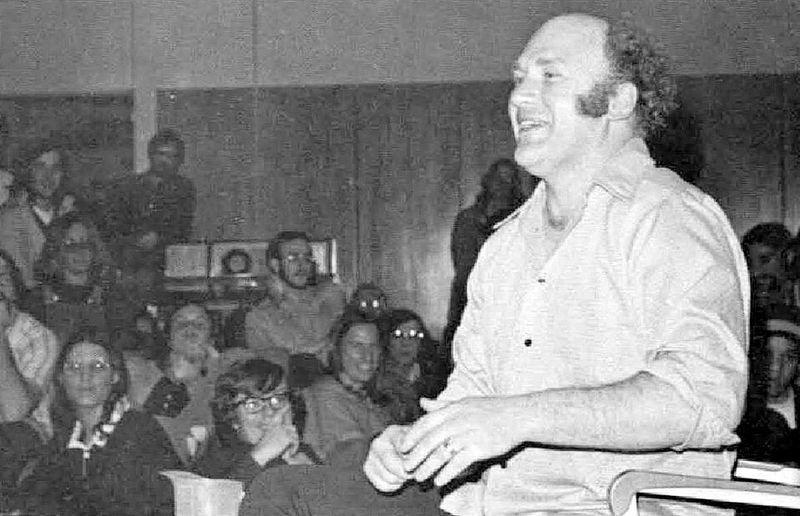

1. Stephen King – The Shining (1980)

King has said Kubrick’s film is visually impressive, but in his view it misses the novel’s warmth and redemptive arc.

Many viewers embraced the film’s imagery and Nicholson’s performance, King felt the emotional core got lost.

He believed the movie turned his story about family and recovery into something cold and distant.

Kubrick’s artistic choices clashed with King’s vision of hope and redemption.

Perhaps that’s why King later made his own TV version to reclaim his original intent.

2. Stephen King – The Lawnmower Man (1992)

King sued to get his name removed from marketing, arguing the movie didn’t meaningfully resemble his story.

His original tale was a simple horror piece about a mysterious gardener with supernatural secrets.

Instead, filmmakers created a sci-fi thriller about virtual reality experiments gone wrong.

Honestly, the two versions shared almost nothing beyond the title.

A judge initially ruled in King’s favor, and on appeal his name could remain on-screen but had to be removed from advertising; the dispute ended with a settlement.

Sometimes protecting your creative reputation means taking legal action.

3. P. L. Travers – Mary Poppins (1964)

Travers objected to major changes and later said she cried at the premiere, describing the tears as bitter.

She fought against the animated sequences and musical numbers that Disney insisted on including.

Her Mary Poppins was meant to be stern and mysterious, not sweet and cheerful.

Travers later framed the moment as disappointment rather than delight.

The film became a beloved classic, but Travers never made peace with it.

Creative differences can hurt deeply.

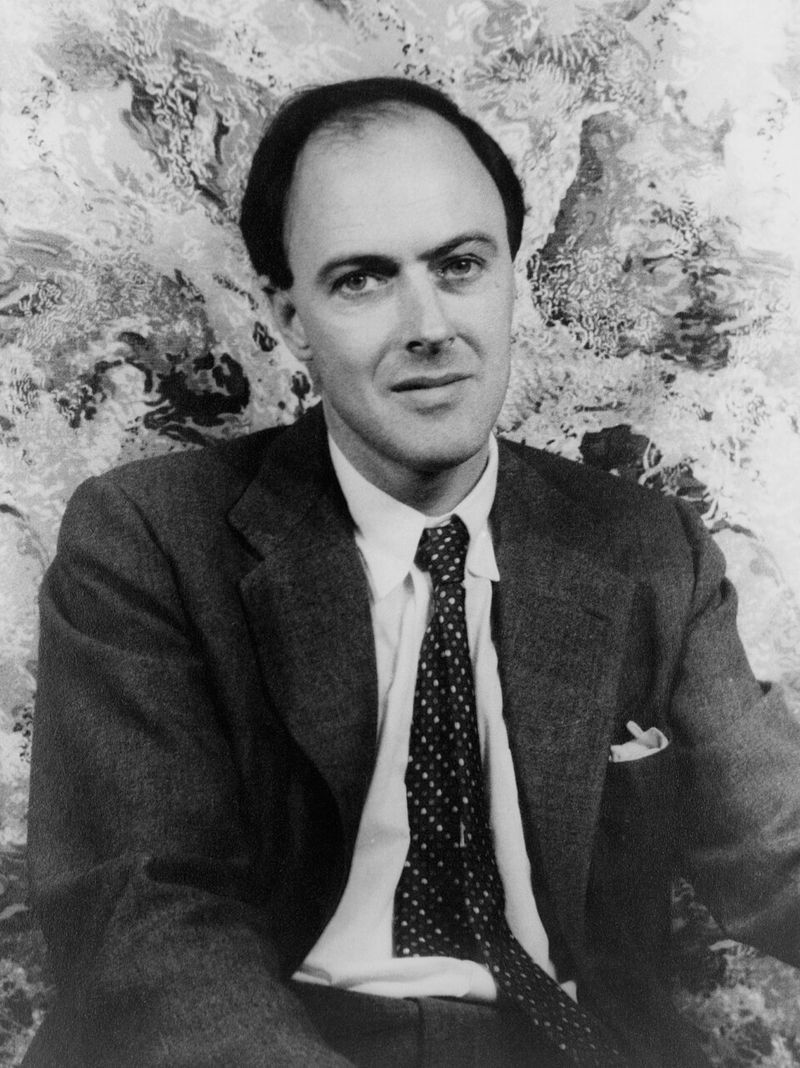

4. Roald Dahl – Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory (1971)

Dahl disliked the 1971 film and became wary of further screen versions of his work.

He objected to plot changes and said the film put too much emphasis on Wonka instead of Charlie, changing his story’s heart.

The screenwriter made adjustments Dahl found unnecessary and annoying.

Gene Wilder’s performance became iconic, but he resisted further film follow-ups connected to the book during his lifetime.

If you write something magical, watching others reshape it can feel like betrayal.

Dahl’s frustration lasted his entire life.

5. Rick Riordan – Percy Jackson & The Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010)

Riordan publicly criticized the film process in emails to producers, objecting to changes like aging up the characters, and he has said he did not watch the finished movies.

Early warnings sent to the studio highlighted serious problems regarding character ages and fundamental plot changes.

Production moved forward regardless of these concerns until viewers eventually noticed the exact issues the author predicted.

Years later, a Disney+ series reboot was developed with Riordan’s involvement and a stated focus on closer fidelity to the original books.

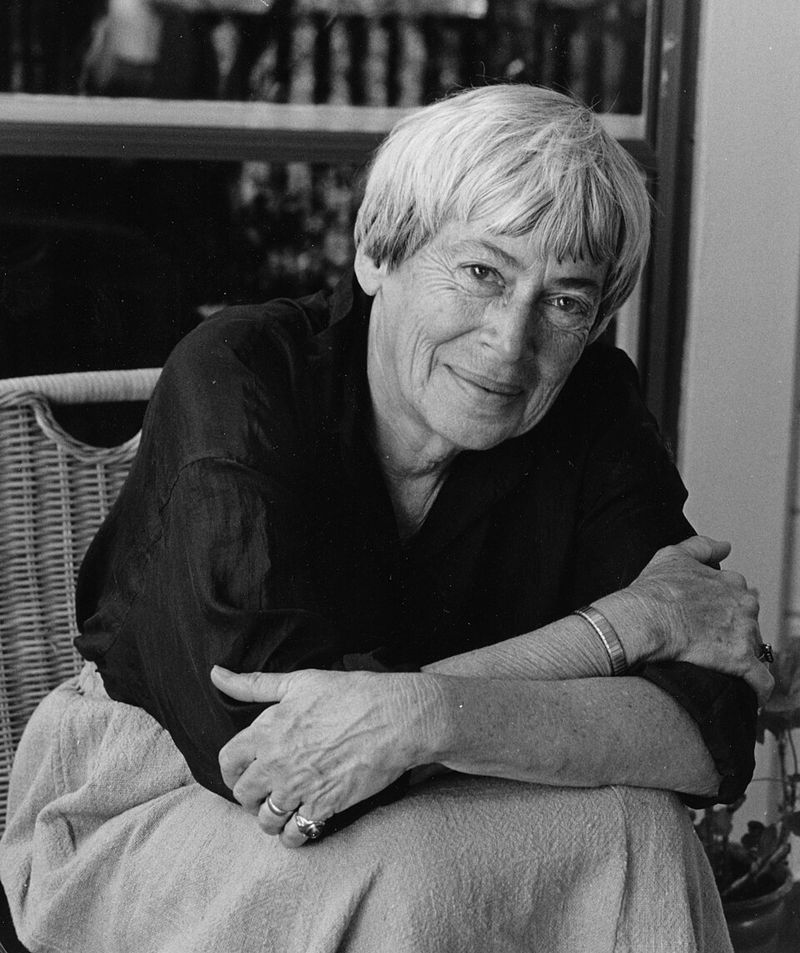

6. Ursula K. Le Guin – Tales from Earthsea (2006)

Le Guin published a detailed response explaining what did and did not feel like Earthsea to her.

Studio Ghibli’s adaptation changed character relationships and themes she considered essential.

She appreciated the animation quality but felt the story became unrecognizable.

Her written critique was thoughtful yet firm, explaining exactly where the film went wrong.

Readers and fans respected her honesty about feeling disappointed.

Maybe speaking your truth matters more than politeness when art is at stake.

7. Ken Kesey – One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

Public disavowals from Ken Kesey followed major narrative changes, specifically the decision to abandon Chief Bromden’s internal perspective.

Original novel chapters told the story through the Chief’s eyes, creating a unique and hallucinatory narrator experience.

Cinematic adaptations shifted focus to make McMurphy the central protagonist, fundamentally altering the author’s intended themes.

Kesey disavowed the film in part because it dropped Chief Bromden’s narration, and reports note he did not embrace the finished movie or approve of the final product.

8. Michael Ende – The NeverEnding Story (1984)

Ende became openly critical and sharply condemned the film’s tone and what he saw as a trivialization of his material.

He believed filmmakers only cared about making money and ignored his book’s deeper philosophical messages.

Ende tried to distance himself from the production after seeing the film.

Though he lost in court, Ende never stopped expressing his disappointment publicly.

The film became a fantasy classic, but Ende saw it as a painful misrepresentation.

Legal battles can’t always heal creative wounds.

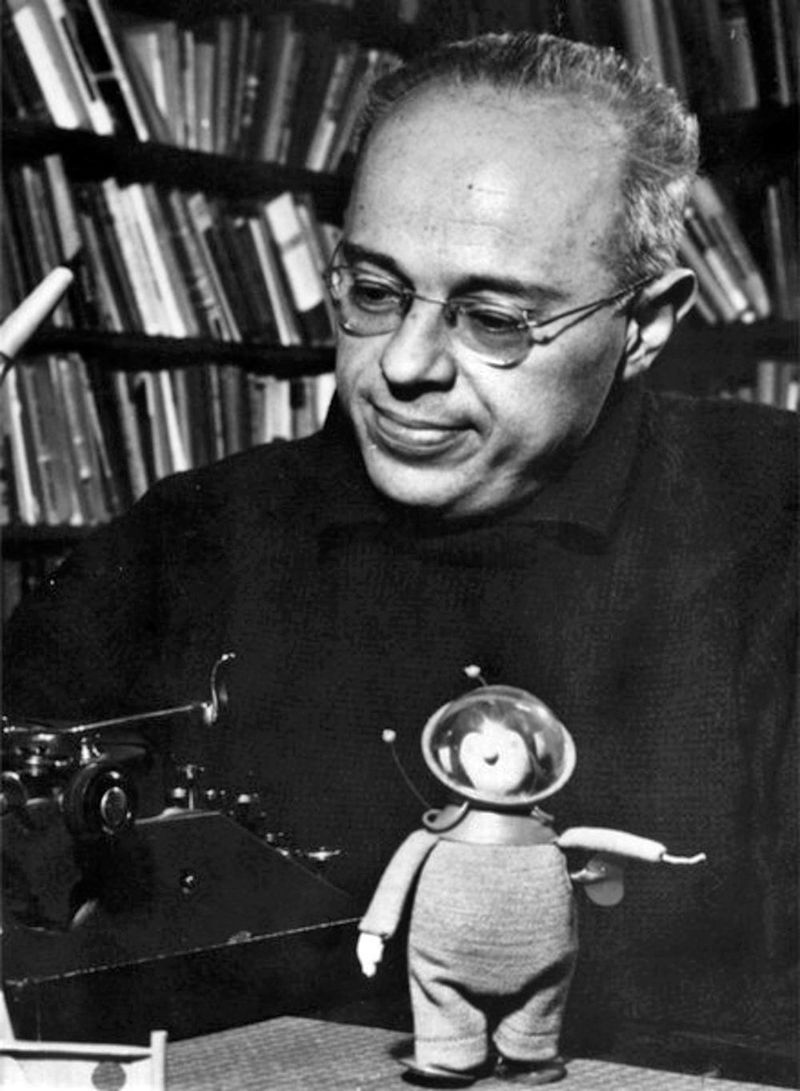

9. Stanisław Lem – Solaris (1972)

Lem disliked Tarkovsky’s interpretation, famously comparing it to ‘Crime and Punishment’ in space and described a fundamental mismatch in what each thought the story meant.

Tarkovsky focused on human emotion and spirituality, while Lem wanted to explore alien consciousness beyond human understanding.

The philosophical gap between author and director proved too wide to bridge.

Lem felt the film turned his science fiction into a romantic drama.

Different artistic visions can create beautiful work that still disappoints its source.

10. Alan Moore – The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003)

Moore has repeatedly distanced himself from screen adaptations and has removed his name from related credits in multiple cases.

He found Hollywood’s approach to his complex graphic novels simplistic and commercially driven.

The League film particularly frustrated him with its action-movie treatment of literary characters.

Moore has said he does not want his name used on adaptations he doesn’t control, and he has declined money connected to some of those projects.

When disappointment runs deep enough, complete separation becomes the only answer.

Artistic integrity sometimes means walking away.

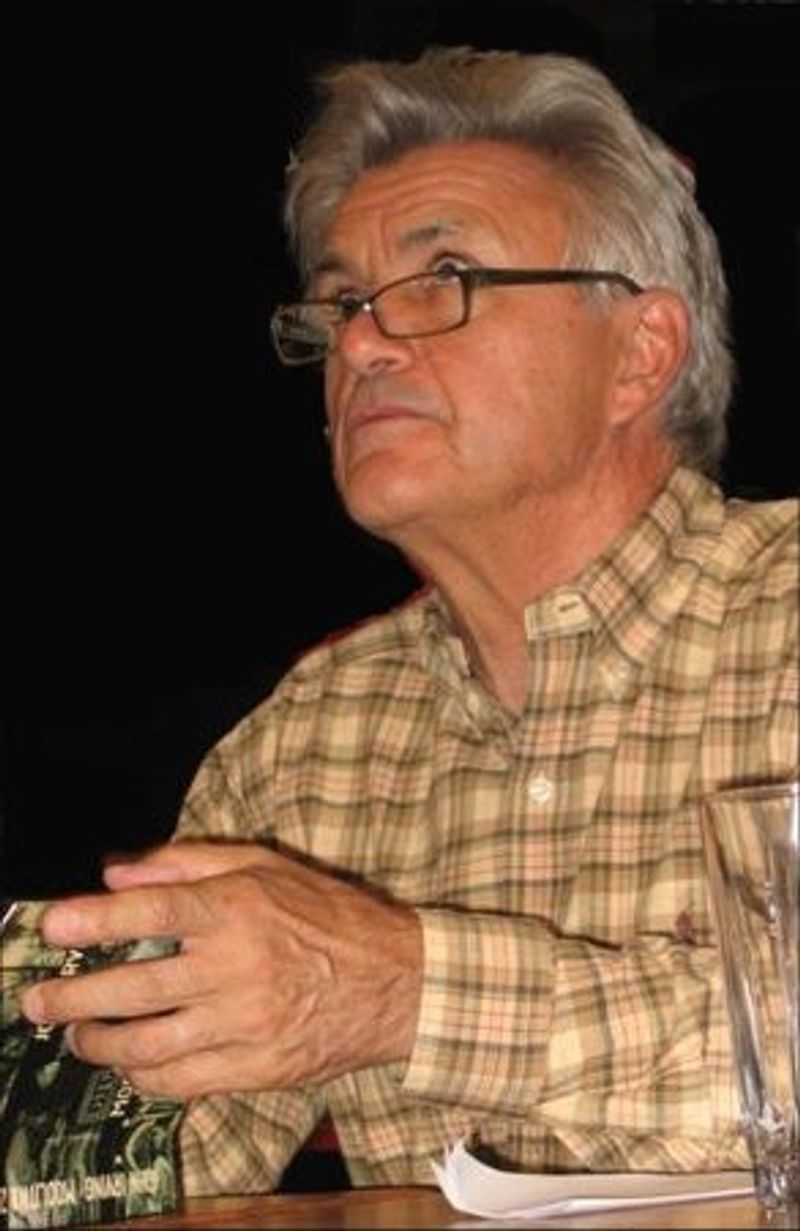

11. John Irving – Simon Birch (1998)

The film’s credits frame it as ‘suggested by’ the novel A Prayer for Owen Meany, reflecting how far the screenplay diverged.

Filmmakers altered the ending, specific character details, and the entire spiritual core of the original narrative.

Support for calling the project a true adaptation vanished once John Irving realized how much the production had strayed.

Small changes in screen billing successfully protected the novel’s reputation while acknowledging a loose connection to the film Simon Birch.

12. Jodi Picoult – My Sister’s Keeper (2009)

Picoult has said the ending change undercut what the story meant to her and that it was a major mistake.

Original story conclusions sparked vital conversations regarding medical ethics and the true meaning of family sacrifice.

Production teams replaced those challenging themes with a more conventionally uplifting and emotionally safe cinematic resolution.

Staying silent felt impossible for the author once the most powerful moment of her work had been erased.

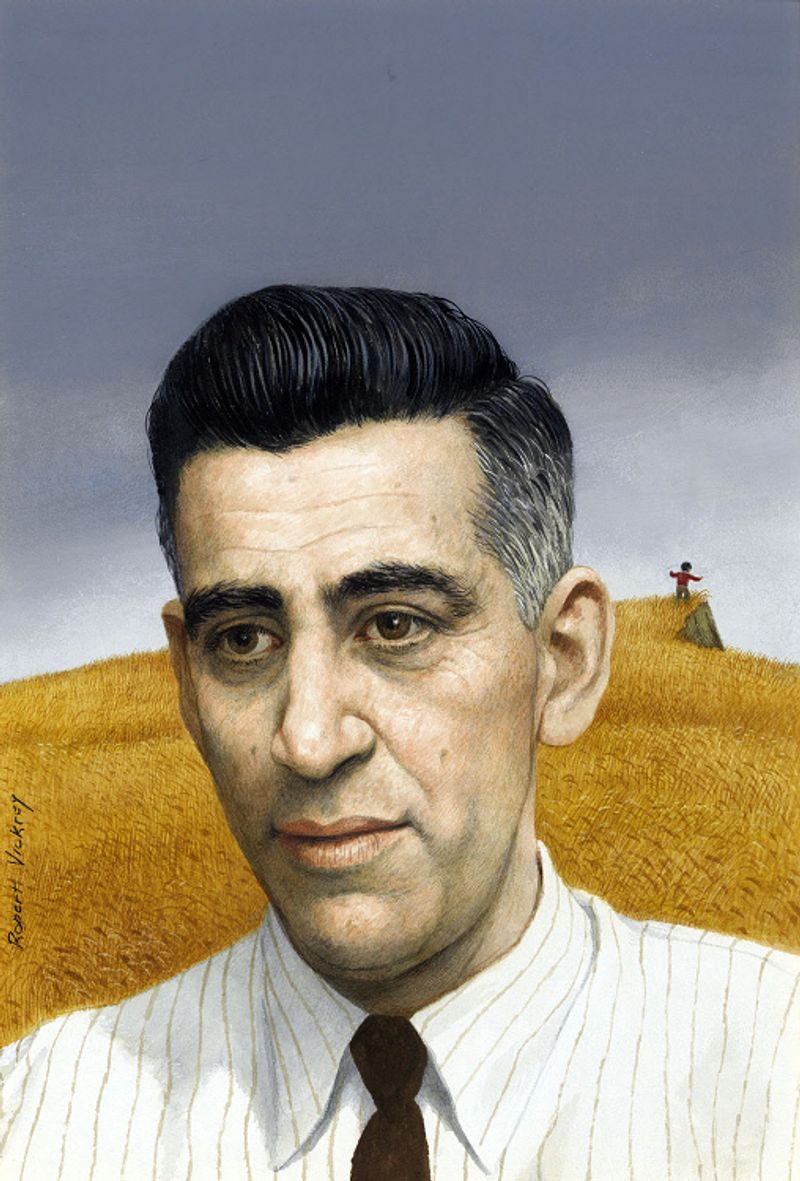

13. J. D. Salinger – My Foolish Heart (1949)

Salinger strongly disliked Hollywood’s treatment of his work, though accounts differ on how completely that experience alone shaped his later stance on adaptations.

The film took liberties with his short story that he found unacceptable and commercial.

Salinger later expressed strong contempt for Hollywood after that experience, but biographical accounts caution against attributing his later policy to this film alone.

Salinger spent decades protecting his work from Hollywood’s reach.

One bad experience can create a lifetime of caution.

Privacy and control mattered deeply to this reclusive author.

14. Ray Bradbury – Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

Bradbury sometimes criticized the film harshly, including a later reported quote that Truffaut ‘ruined’ it, even though the movie has remained influential with critics.

Frustrations mounted throughout production as the author felt the French director missed the inherent urgency and danger within his dystopian warning about censorship.

Creative differences and significant language barriers further complicated the process of translating the novel’s themes to the screen.

Artistic disagreements often transcend nationality, proving that even respected directors can overlook what an author considers essential to their work.