15 Movies With Themes Similar To Netflix’s Guillermo Del Toro Frankenstein

Playing god never goes according to plan. Stories about creation, ambition, and unintended consequences tap into some of our deepest fears.

When the line between monster and human starts to blur, the horror hits on a whole different level. If that dark, emotional edge pulled you in, there are more films that explore the same chilling ideas.

Note: This article is provided for general informational and entertainment purposes and reflects a thematic comparison of films, not an official recommendation or content rating.

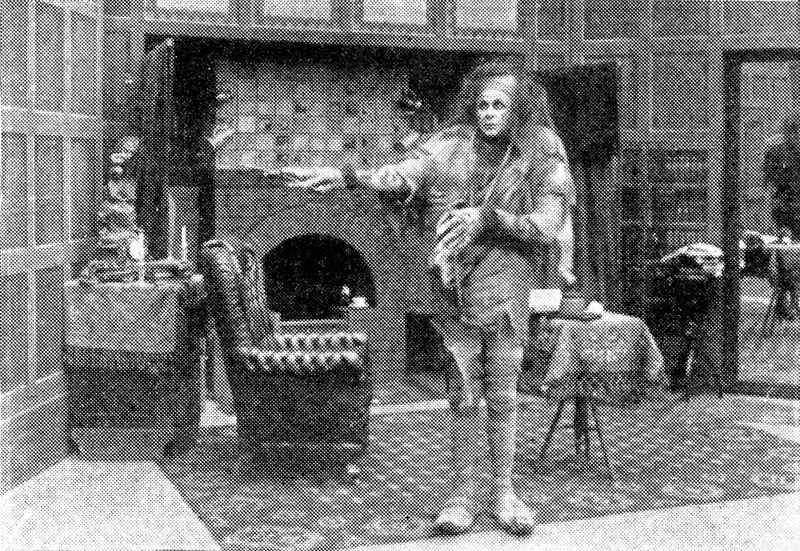

1. Frankenstein (1931)

Before del Toro’s version, there was James Whale’s groundbreaking film that introduced the world to Boris Karloff’s iconic portrayal of the Monster.

The flat-topped head, neck bolts, and lumbering walk became the template everyone thinks of when they hear the name Frankenstein. Whale’s direction turned a horror story into a tragedy about loneliness and rejection.

The film’s expressionistic shadows and atmospheric laboratory scenes still influence filmmakers today. It’s the grandfather of monster movies and remains surprisingly moving nearly a century later.

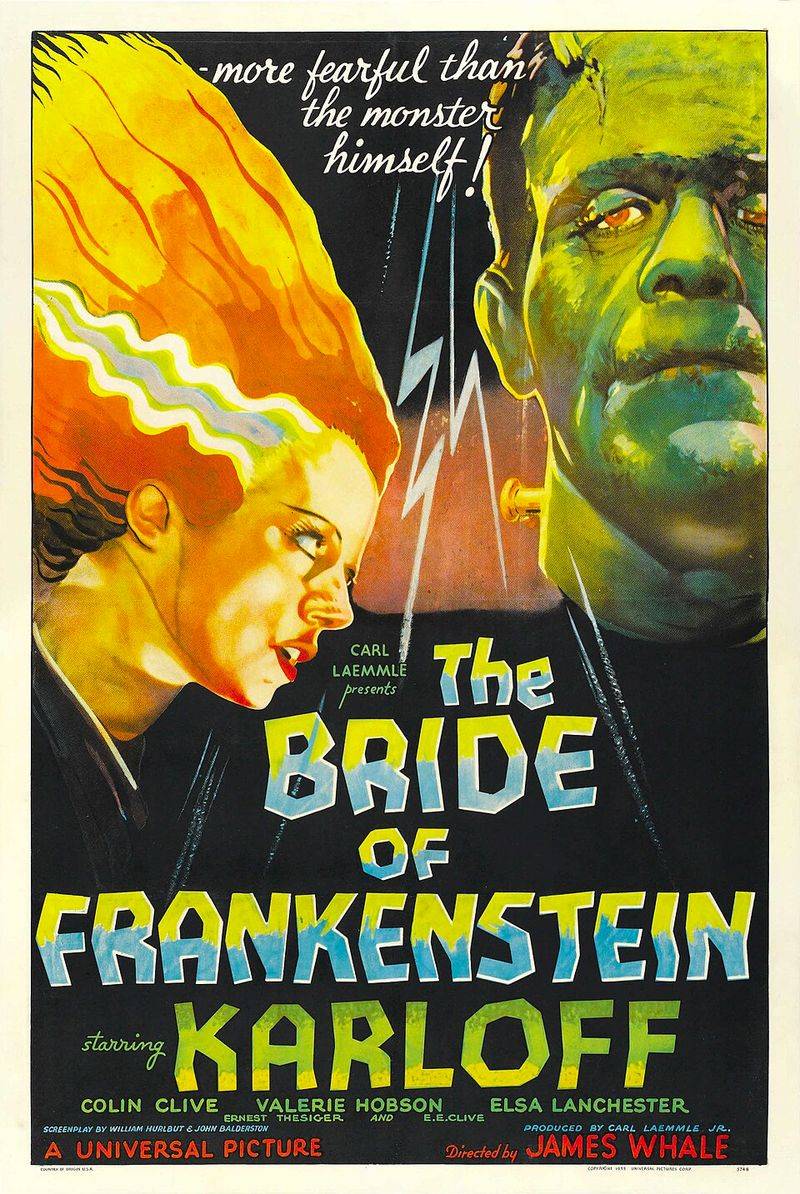

2. The Bride Of Frankenstein (1935)

Often considered even better than the original, this sequel picks up right where the first film ended. The Monster survives and desperately seeks companionship, leading Dr. Frankenstein to create a mate for him.

Elsa Lanchester’s performance as the Bride is unforgettable despite her brief screen time.

The film deepens the themes of isolation and belonging while adding dark humor and spectacular special effects for its era. It’s a masterclass in how sequels can expand on original ideas rather than just rehash them.

3. Son Of Frankenstein (1939)

What happens when the next generation inherits a legacy of horror?

Basil Rathbone stars as Henry Frankenstein’s son, who returns to the family castle only to discover the Monster still lives. Bela Lugosi delivers a creepy performance as the broken-necked Ygor who has befriended the creature.

The film explores how family reputation and past mistakes haunt the present.

While not as critically acclaimed as the first two films, it offers fascinating commentary on inherited guilt and the weight of family expectations that still feels relevant today.

4. Frankenstein (1910)

Long before talkies, Thomas Edison’s studio produced the very first film adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel.

Running about 16 minutes, this silent short film used early trick photography to show the Monster’s creation in a bubbling vat. The makeup and effects were primitive by modern standards but groundbreaking for 1910.

The short was long believed lost until a nitrate print held by a Wisconsin collector surfaced publicly in the mid-1970s. Watching it today feels like stepping into a time machine to see how horror cinema began.

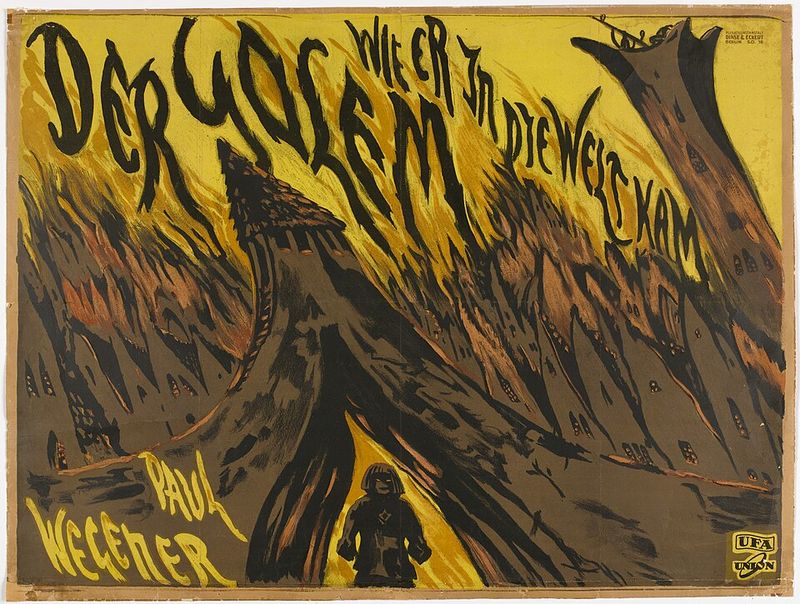

5. The Golem How He Came Into The World (1920)

German expressionist cinema gave us this tale of a rabbi who creates a clay giant to protect Prague’s Jewish community from persecution.

Like Frankenstein’s Monster, the Golem becomes dangerous when it develops feelings beyond its creator’s control. The film’s angular sets and dramatic shadows influenced countless horror movies that followed.

Paul Wegener’s performance as the lumbering clay creature conveys surprising emotion despite heavy makeup.

It’s a powerful meditation on creation, protection, and how good intentions can lead to tragic outcomes when we play with forces beyond our understanding.

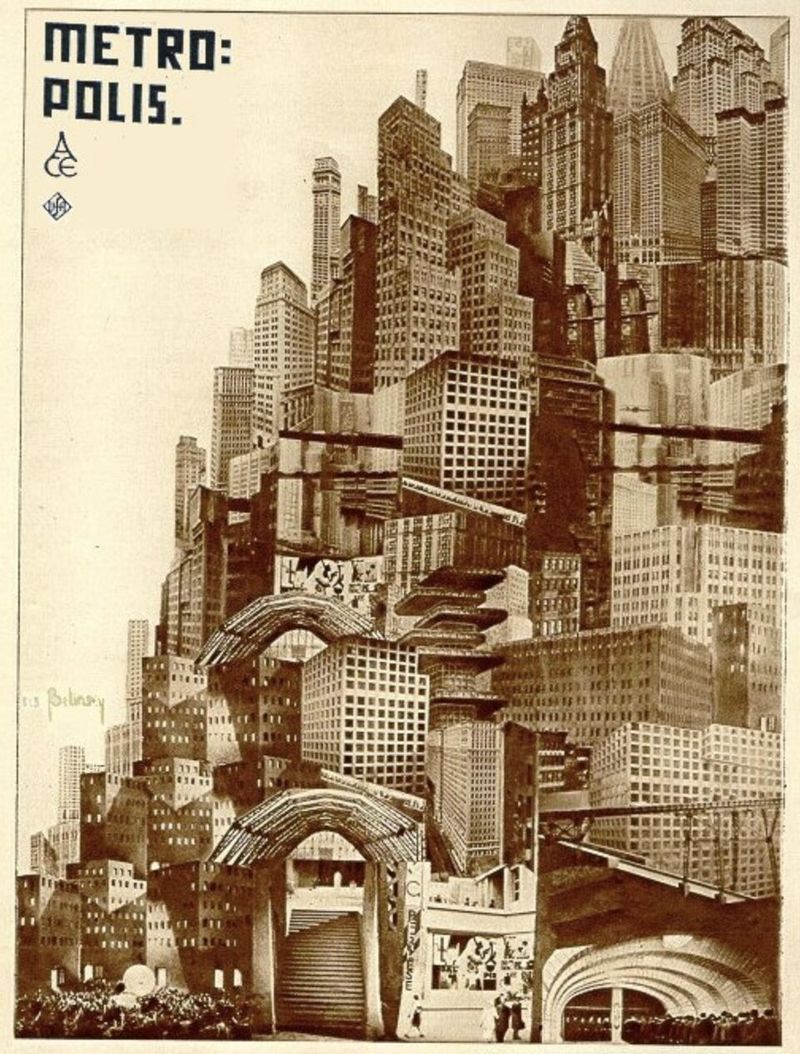

6. Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang’s science fiction masterpiece shows a gleaming future city divided between wealthy elites and exploited workers.

When a mad scientist creates a robot duplicate of the compassionate Maria, chaos erupts throughout Metropolis. The robot’s creation scene, with electrical arcs and bubbling machinery, directly inspired countless Frankenstein films.

Beyond the stunning visuals, the film explores how technology can be used to manipulate and control rather than liberate.

It’s a cautionary tale about class division and the dangers of creating artificial life without considering the moral implications.

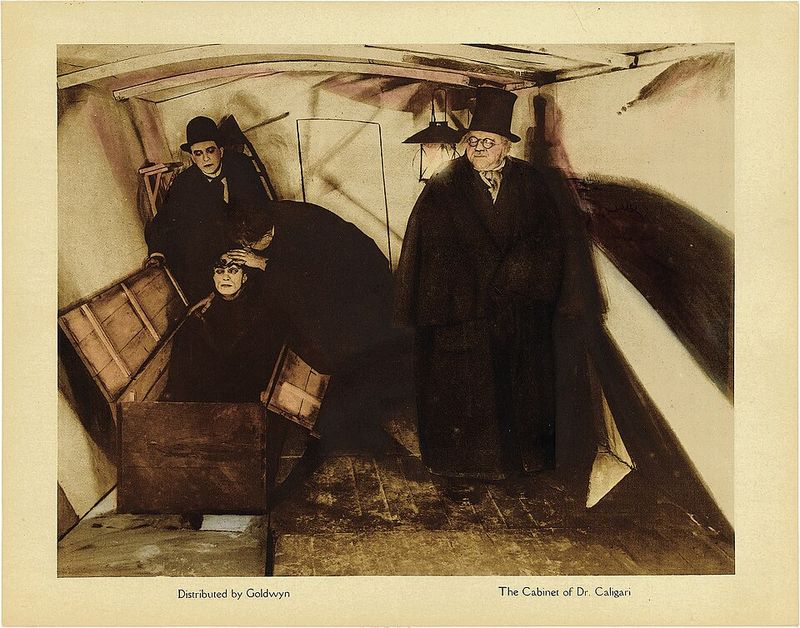

7. The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari (1920)

A nightmare takes shape on film through twisted buildings, sharp angles, and a hypnotist who commands a sleepwalker to commit murders.

As a landmark of German Expressionism, the film shaped horror cinema’s visual language for generations.

Dr. Caligari’s control over the somnambulist Cesare echoes Frankenstein’s bond with his creation, both centered on figures who dominate beings without real autonomy.

Few audiences expected the story’s shocking twist ending, which dares to question reality itself.

Painted sets and exaggerated performances build an atmosphere that still feels deeply unsettling more than a century later, proving that bold style and psychological horror endure longer than simple jump scares.

8. Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde (1931)

Fredric March earned an Oscar for his chilling dual performance as the respectable Dr. Jekyll and the monstrous Mr. Hyde. Instead of creating life outside himself like Frankenstein, Jekyll’s experiments release the darkness already buried within.

Transformation scenes relied on innovative color filters and makeup techniques that stunned audiences in the 1930s.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s tale probes how ambition and curiosity can twist even the noblest intentions. Lingering questions about whether evil is made or merely uncovered echo the same moral unease found in Frankenstein stories.

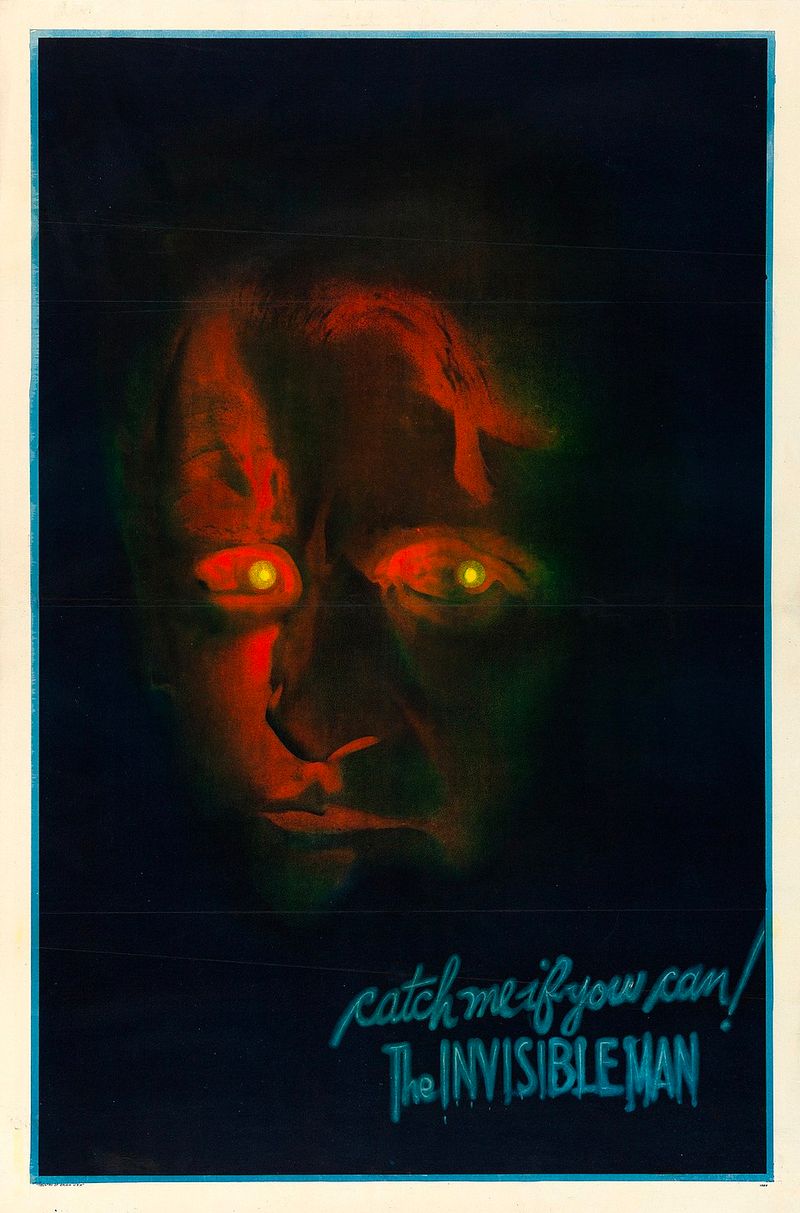

9. The Invisible Man (1933)

Claude Rains delivers an incredible performance in a role where you mostly only hear his voice.

A scientist discovers invisibility but the process drives him mad with power and paranoia. Like Frankenstein, it’s a story about scientific breakthroughs that come with terrible psychological costs the inventor never anticipated.

The special effects were revolutionary for 1933, making objects float and showing empty clothes walking around.

Director James Whale brought the same Gothic atmosphere he perfected in Frankenstein, creating another tale of ambition, isolation, and the thin line between genius and madness that destroys everything it touches.

10. Island Of Lost Souls (1932)

Perhaps no film captures Frankenstein’s themes of playing god quite like this adaptation of H.G. Wells’ “The Island of Dr. Moreau.”

Charles Laughton plays the ruthless Dr. Moreau, who surgically transforms animals into human-like beings on a remote island. The beast-men’s chant of “Are we not men?” is heartbreaking and horrifying.

The film faced censorship and bans, including in the UK, in part because censors objected to its taboo implications and the film’s disturbing medical-horror elements.

It’s a brutal examination of creation, cruelty, and what defines humanity that makes Frankenstein’s experiments look almost tame by comparison.

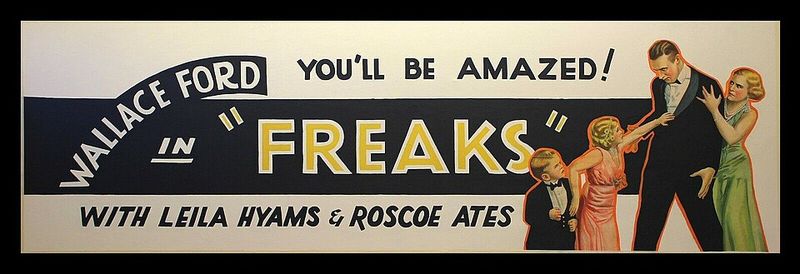

11. Freaks (1932)

Tod Browning’s controversial masterpiece featured real circus performers with physical differences in a dark story of betrayal and revenge.

A beautiful trapeze artist schemes to murder a little person for his inheritance, only for the circus performers to answer with terrible vengeance. Instead of a tale like Frankenstein, the true monsters here are the seemingly normal people who exploit and ridicule others for being different.

For decades, censors kept the film banned because of its unsettling subject matter.

Modern audiences often view it as a compassionate portrait that challenges viewers to question whether monstrosity lies in appearance or in cruel actions.

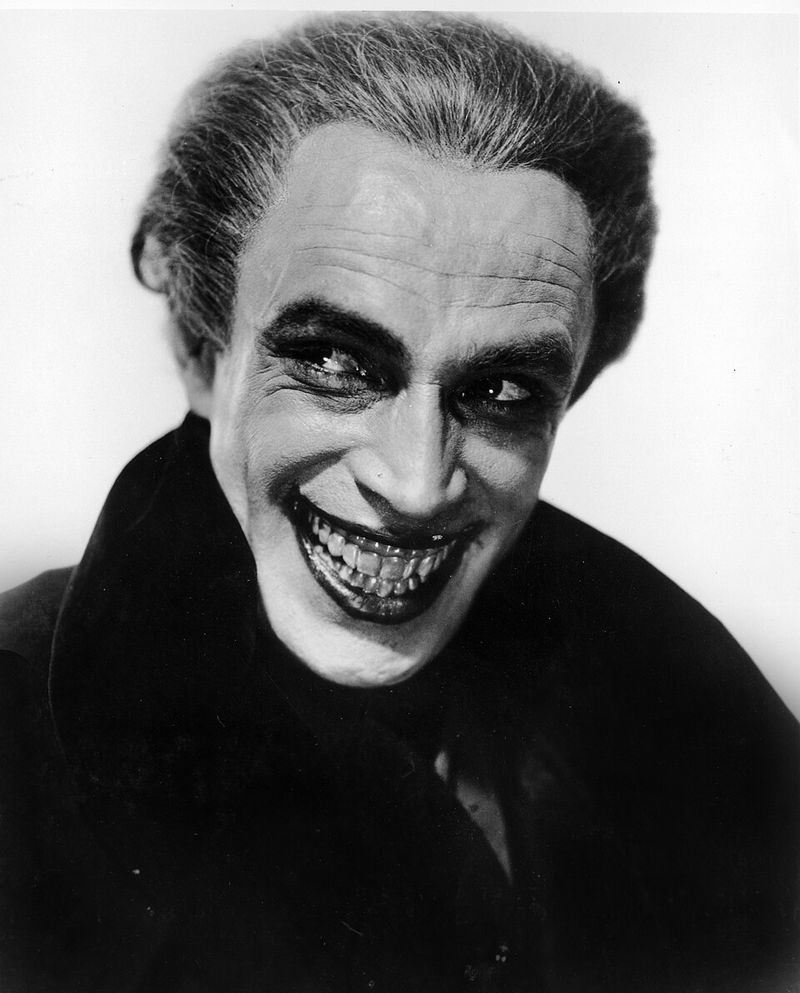

12. The Man Who Laughs (1928)

Conrad Veidt stars as Gwynplaine, a man whose face was surgically carved into a permanent grotesque grin as a child.

Despite his horrifying appearance, he has a gentle soul and finds love with a blind girl who can’t see his disfigurement. The character directly inspired Batman’s Joker, but this story is pure tragedy rather than villainy.

Like Frankenstein’s Monster, Gwynplaine is judged entirely by his appearance despite his humanity.

The film explores how society creates monsters through cruelty and rejection, making it a powerful companion piece to any Frankenstein adaptation that emphasizes the creature’s suffering.

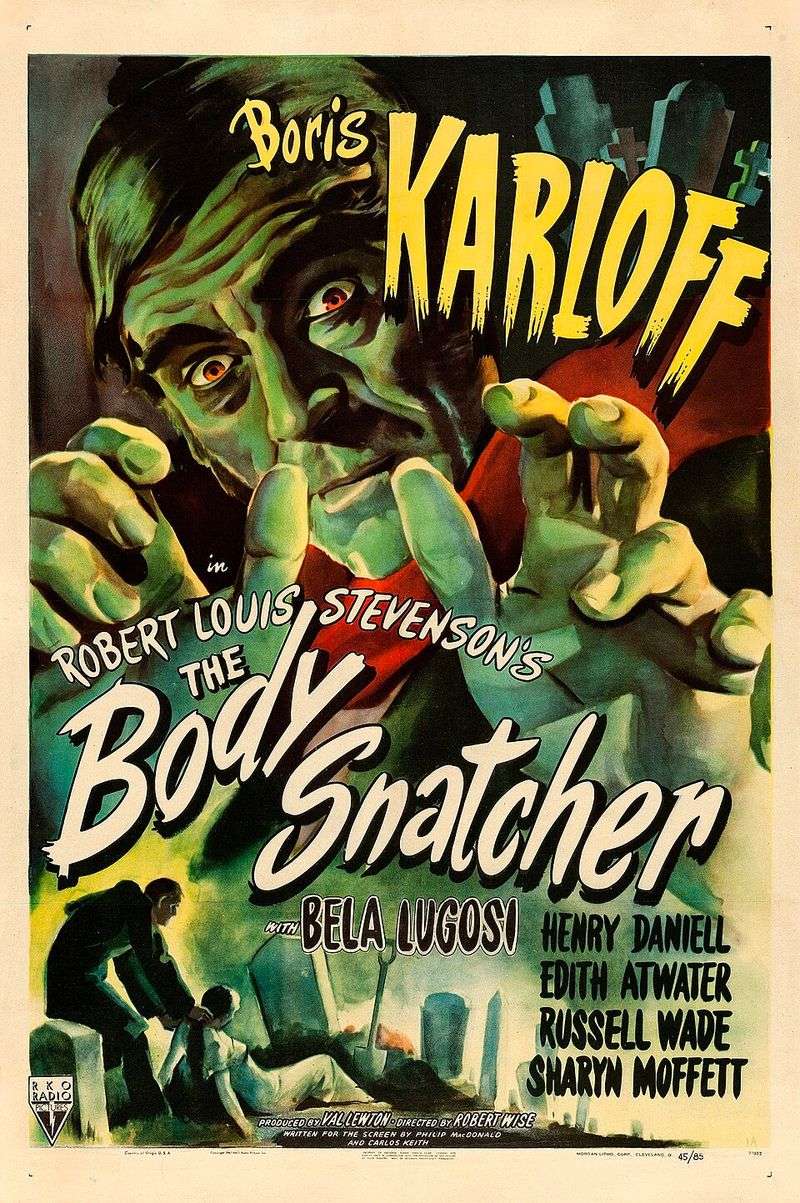

13. The Body Snatcher (1945)

Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi reunite in this chilling tale based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s story inspired by real grave robbers.

A medical student becomes entangled with a cabman who supplies fresh corpses for anatomical study, but the source of these bodies grows increasingly sinister. The film explores the moral compromises made in the name of scientific advancement.

Like Victor Frankenstein raiding graveyards for body parts, these characters justify terrible acts as necessary for medical progress.

Producer Val Lewton’s atmospheric direction creates dread through suggestion rather than explicit gore, making the horror feel more psychological and disturbing.

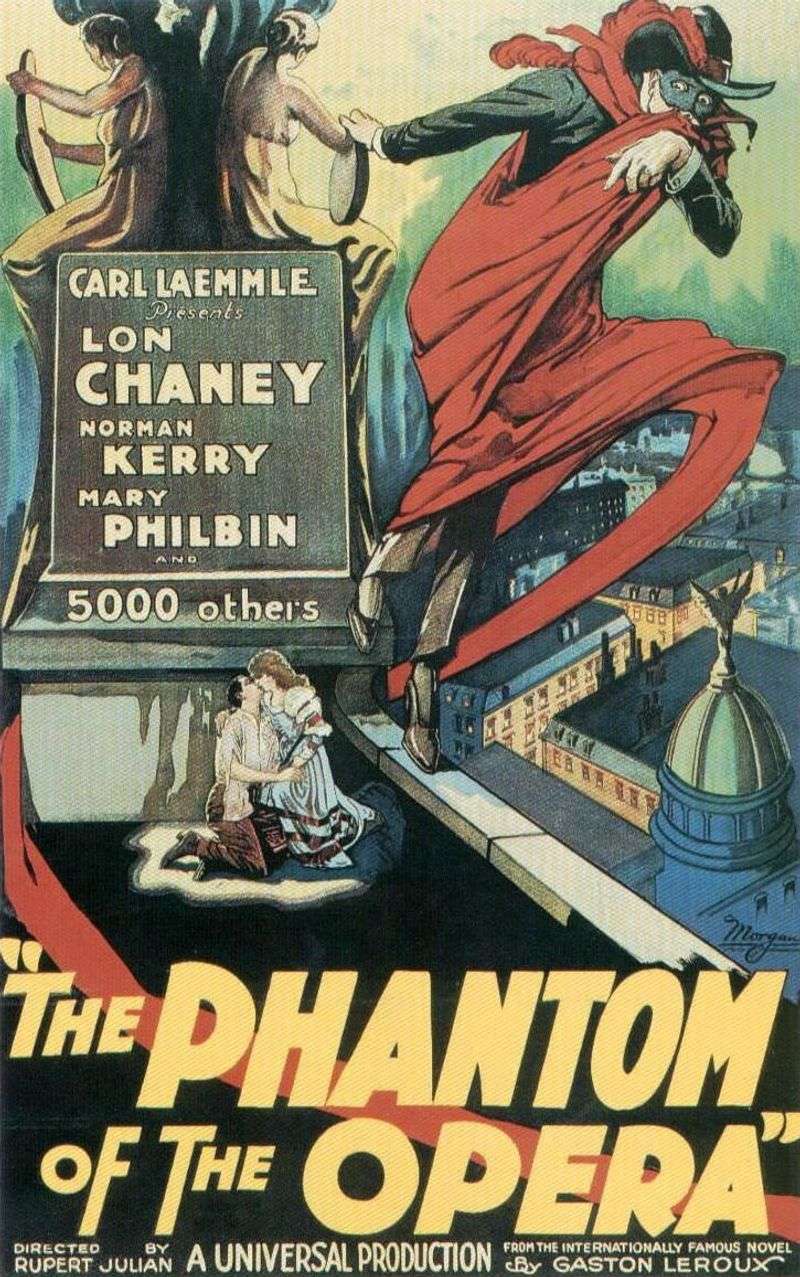

14. The Phantom Of The Opera (1925)

Lon Chaney’s self applied makeup as the disfigured Phantom still ranks among cinema’s most shocking reveals nearly a century later. Inside the Paris Opera House, the Phantom obsesses over a young soprano whose career he secretly guides from the shadows.

When his mask is ripped away, audiences confront a skull-like face Chaney achieved with practical makeup techniques, including wires concealed under putty to shape his nose.

Much like Frankenstein’s Monster, the Phantom stands as a tragic figure whose appearance has pushed him to society’s margins.

Brilliance and a deep capacity for love become buried beneath a frightening exterior, driving violence born from loneliness and rejection that echoes themes in Shelley’s novel.

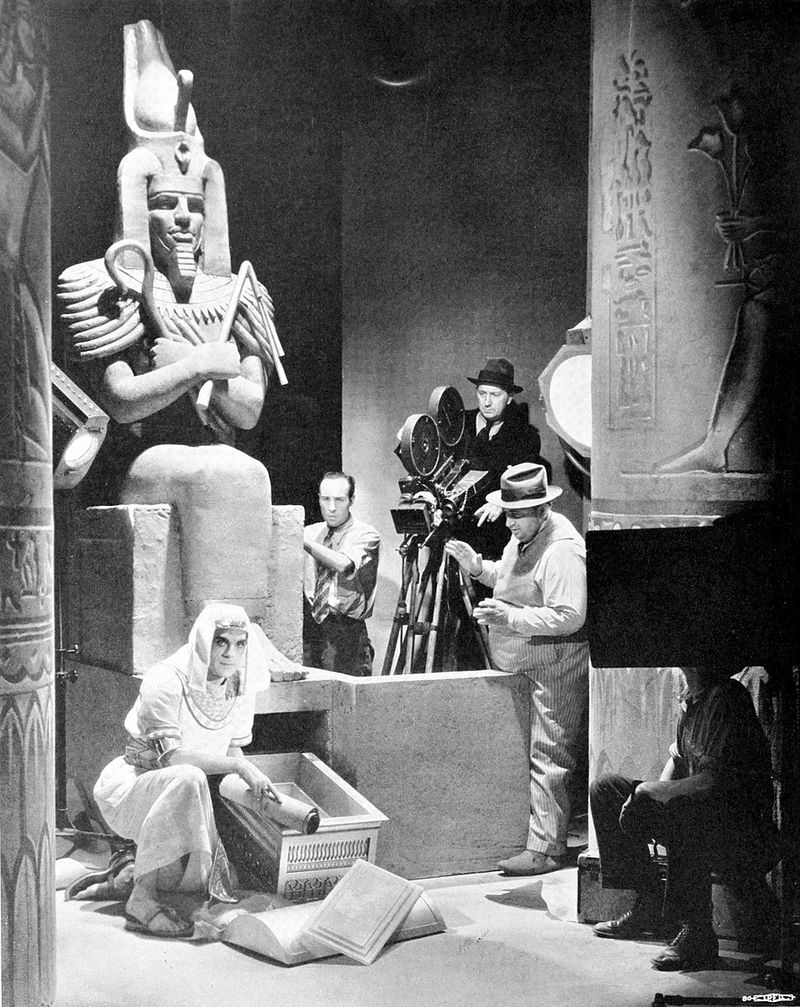

15. The Mummy (1932)

Boris Karloff swaps Frankenstein’s bolts for ancient bandages in a story about an Egyptian priest brought back to life after 3,700 years. Buried alive for trying to revive his forbidden love, Imhotep returns when archaeologists accidentally awaken him and then seeks out her reincarnation.

One of horror cinema’s most memorable openings shows a man reading a resurrection scroll while Karloff’s mummified hand slowly begins to move. Similar to Frankenstein, the tale explores the consequences of defying death and the peril of obsessive love.

True tragedy rests in Imhotep’s refusal to accept that certain parts of the past are meant to stay buried.